In this introduction, we provide an overall framing of the articles that follow by placing the Ukraine conflict which today embroils the West in confrontation with Russia, within an historical account of the geopolitical economy of contemporary capitalism and the dynamics of imperialism in the twenty-first century, taking particular account of the decline of US and Western power and the rise of other centres of economic and military power, which are able to resist and contest Western power.

We pay particular attention to how today’s geopolitical flashpoints, of which Ukraine is among the most critical, emerged to belie post-Cold War expectations of a “peace dividend” and a “unipolar” world, clearly distinguishing the US and the EU roles in these processes. Given the widespread tendency in the West to label Russia “imperialist,” particularly after the integration of Crimea into the Russian Federation, we end our discussion with a consideration of this question which concludes that the term, while it continues to be an appropriate description of the pattern of Western actions, is not so for that of Russian ones.

Since November 2013, when the Maidan protests unseated the Yanukovich government for its reluctance to sign the EU accession treaty, events have taken a tumultuous course in Ukraine. In the ensuing civil war Crimea transferred its allegiance to Russia, parts of the East entered a protracted military conflict with the Kyiv regime and Ukraine became major flashpoint in rising international tensions between the West and Russia. The confrontation is sufficiently serious that both Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk and former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev—warned that it could spark a new, nuclear,World War (see also van der Pijl 2016).

Advancing under the usual banners of democracy and self-determination, the West sponsored regime change to install a new government friendlier to the West and more open to EU and NATO membership, which also contained members of extreme fascistic groups including the Right Sector and Svoboda. The Western-dominated IMF also extended a $17 billion loan to the new regime, the first time it has ever extended a loan to a country in civil war. Meanwhile expectations that Russia would follow up its support for Crimea with aid to the rebels in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions, fired by a vision of an autonomous (but not necessarily sovereign) “Novorussia,” which would preserve their productive economy as well as linguistic and other rights, were disappointed and its social radicalism curtailed by Russian actions (Clarke in this issue). By early 2016, the situation seemed stalemated and by summer, while NATO massed troops up and down Russia’s Western frontier in the run-up to its Warsaw summit, the British vote in favour of leaving the European Union opened up a host of new questions about the economic and military links between the continental European and the Anglo-American parts of the Western alliance and whether further Eastern expansion remains on the cards.

Given the number of questions that still hang over the Ukraine imbroglio, not to mention the configuration and dynamics of the world order, this issue seeks to shed light on key aspects of the Ukrainian crisis and its international dimensions. There have been others. There are, of course, the usual tendentious works, such as Edward Lucas’s attempt ([2008] 2014) to steel Western resolve by one-sidedly celebrating the Maidan protests as a “democratic revolution” if “chaotic in places, with some admittedly troubling fringe elements” (xvii) and condemning Russia as irredeemably authoritarian, corrupt and expansionist, a modern day Tsardom.

This sort of rhetoric appeals to both the liberal interventionists and the neoconservative unilateralists in the US policy-making establishment. However, thanks to the growing list of US military and foreign policy failures, a new “realist” school now frontally criticizes the irresponsibility and provocation of US policy (Mearsheimer 2014) and arrives a more nuanced analysis. Ironically this “realist” analysis relies on two rather unrealistic assumptions—that “Russia is a declining power, and it will only get weaker with time” and that Ukraine is not a “core strategic interest” for the West —that Western actions have demonstrably belied (Mearsheimer 2014, 88).

If Lucas’s work essentially articulates standard US policy for the Ukraine case, the EU also has its intellectuals who essentially make a case for Ukraine’s integration into the Union which calls up visions of prosperity and stability (Åslund 2015), entirely ignoring the reality of economic devastation and political chaos that nations hitherto even more prosperous and productive than Ukraine, pre-eminently Greece, have already been subject to in the European Union and the Eurozone. They also ignore the gravely adverse effects of severing the critical historic links between the Ukrainian and Russian economies.

Another genre of writing on the current crisis in Ukraine is the work of old Russia hands in the West who recall the optimism that surrounded the early post-Cold War years and the prospects of increasing closeness between Russia and the West as the essential

backdrop for their narratives of how matters went downhill from there. They speak with knowledge of the actors involved and seek to chart ways back to that original optimism (Levgold 2016; Matlock 2010).

While there are indeed some works that aim to provide a guide to the complex history of Ukraine and the current crisis and challenge many Western myths about Ukraine, they typically lack a focus on the political economy of the region (Pikulicka and Sakwa 2015; Sakwa 2015) or of the volatile geopolitical economy of imperialism in an age of increasingly multipolarity (Yekelchuk 2015). Unless the confrontation in Ukraine is placed in these contexts, it is hard, if not impossible, to grasp the causes and dynamics of the social and military evolution of the crisis or the seriousness of the confrontation over Ukraine and the potential it contains for war.

Against this literature, our contribution can be distinguished in a number of importantways. It arises from a grass roots initiative taken at the very beginning of the rebellion in Donetsk and Luhansk. A “school” for activists and social organizations from all over Ukraine was held in Belgorod. They shared broadly progressive views, aiming to develop and defend the welfare state and other progressive policies and institutions in all parts of Ukraine and beyond. In discussions of major issues and strategies, participants decided that they needed to formulate a common platform and consolidate the identity of a progressive, socially oriented coalition going beyond defending Russkiy Mir (Russian world, or Russianness). Focused as they were on social and economic issues, turning away from the narrow cultural focus of so many Maidan activists, the participants resembled the sort of progressive coalition of leftists and social populists not unlike that which powered the Bernie Sanders campaign in the US. Certainly they felt part of a wider global trend against the sort of neoliberalism that the EU project represented. Anna Ochkina (in this issue) further describes, analyses and reflects on their views and motivations.

The school ended with two statements, an international declaration and a domestic programme designed by Ukrainians for Ukraine. This programme, which continues to circulate around Ukraine, stressed the need for social transformation, democratization and cultural equality of all languages (not just Russian and Ukrainian) as the only way to overcome the crisis. It refrained from mentioning Novorossia as a state though it did mention Novorossia as an idea. In doing this, the signatories were indicating that their programme could be realized in any one of a number of possible state frameworks, including a united federal Ukraine or one divided between autonomous states.

A meeting in Yalta, called jointly by Ukrainian and Russian supporters of the declarations, was convened in June 2014. It brought many of these together with activists and scholars from other parts of the world, allowing the latter vital access to discussions among grass-root Ukrainians. This gave them a very different understanding of the way developments were unfolding on the ground in eastern Ukraine, Crimea and other parts of Ukraine than that provided by or via either Western or Russian official sources.

Though the movement in Ukraine itself was politically defeated both inside the republics and suppressed outside it, its participants remain active and in contact. This issue is a fruit of their work. Another initiative, taken by Roger Annis, who was present at Yalta, is the New Cold War: Ukraine and Beyond website (www.newcoldwar.org) which “aims to provide accurate factual information about the Ukraine conflict and its rapidly-widening consequences.”

Bringing together contributions from many who were present at Yalta and/or Belgorod with some others, this issue is unique in presenting views that either arise from the grassroots or scholars who have an appreciation of developments on the ground in Ukraine. As such, it contains critical new perspectives such as that on the rebel movements in the Donbass; they appear here as proto-revolutionary in that they lack the level of consciousness and leadership that accompanied the classic revolutionary movements. This issue also casts entirely new light on the nature and dynamics of the resistance, its political economy and geopolitical economy. Many of the chapters provide, for the first time in English, inside accounts of the social character, political aims and internal politics of the resistance movements.

Second, while many emphasize that the international crisis unfolding in the eastern edges of Europe involves not only the civil war in Ukraine but rising tensions between Russia and the West, this issue, particularly Boris Kagarlitsky’s contribution, gives readers a complex understanding of how domestic politics and political economy in the two countries are intertwined. This understanding forms the background against which to understand international developments.

Third, this issue provides an understanding of the Ukraine crisis and international tensions between the West and Russia within an updated historical materialist account of imperialism (in this introduction and in the contributions by Buzgalin et al., and Lane).

It also deals with the intertwined questions of how exactly Western actions are part of a broader imperialist project, which is connected with the forms capitalism takes in the core Western countries and whether Russia is imperialist, as so many in the West, neoconservative, liberal or realist, allege. Finally, by putting the Ukraine crisis within this broader understanding of imperialism,

this chapter also relates it to the widening circles of crisis, which characterize our transitional times.

This introduction seeks, inter alia, to clear the way to a better understanding of the geopolitical economy of contemporary capitalism and the dynamics of imperialism in it, particularly as they touch on the Ukraine conflict. We begin by outlining the geopolitical economy of the capitalist world in a longer historical perspective and the postwar period. We then examine the post-Cold War context in which this crisis has germinated and identify the circumstances and motives of key actors. We end the introduction by assessing claims that modern Russia is a new imperialist power today.

The Parabola of Capitalist Imperialism

No greater harm has been done to our understanding of the workings of the capitalist world order than by the exaggeration of the power of the US and the West in the proliferation of writing on “empire” and imperialism with the advent of George Bush Jr’s “imperial” presidency. For just about then, it was entering a steep decline with the rise of China and other emerging economies, a fall which the 2008 financial crisis and accompanying stagnation in the West only accelerated. An entirely new approach to understanding the capitalist world order, its contemporary dynamics, the patterns of imperialism in it and their relation to those of the past, and to capitalism is indispensable for an understanding of the stakes in the confrontation over Ukraine and its role in the wider scenario of confrontations and interventions through which the US and the West seek to retain

their purchase on developments.

These have been militarily sharpest in the Middle East and Africa, with increasing signs of bellicosity in the “Pivot to the Pacific” and the consequent souring of US-China relations (Woodward 2017). They have also surfaced in escalating economic discordances between the West and the BRICS countries, whether at the WTO (Abbas 2016), in the governance of the IMF and the World Bank, within Europe in relations between its core and periphery countries (Serfati 2016) and, in the face of dog-in-the-manger Western intransigence, in the emergence of alternative institutions of international economic governance —from regional trade agreements to initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Western economic policies of austerity have not only mired the West itself in stagnation, the malign consequences of its exported form, structural adjustment, have also provoked a tide of popular revolts against them from the Latin American Bolivarian governments to the Arab Spring. Today, the potential for such popular opposition to Western policies is present in domestic battles around economic policy taking place not only in developing countries from Bangladesh to Brazil but also in the West itself as the Sanders, Trump and Corbyn phenomena suggest.

While the neoconservative celebration of US empire could hardly be expected to shed light on the mechanics of imperialism, the considerable Marxist writing on the subject too, while not without its insights—the rising importance of outright dispossession in twentyfirst century capitalism and that of the control of Middle Eastern oil in the case of David Harvey’s work (2005), for instance—on the whole refrained from any theoretical engagement with Marxist understandings of imperialism. A considerable amount of left writing focused on “financialization” but even the most sophisticated failed to give a proper account of the phenomenon under consideration (Lapavitsas 2009, 2010; for a critique, see Desai and Freeman 2011) in Marxist (or the very compatible Keynesian) terms, let alone connect it to the volatile and destructive dynamics of the dollar-denominated system of money and finance.

Though the left has long recognized that capitalism and imperialism have always been intimately linked and that the latter does not operate through markets alone, critical approaches to imperialism remain divided and hazy about the nature of postwar imperialism, and susceptible to the obscurantist influence of the US discourses of US “hegemony” “globalization” and or “Empire.” Perhaps the most fundamental reason is that while Marx and the theories of imperialism in the early twentieth century understood the drivers of modern capitalist imperialism to be capitalism’s contradictions, in particular its tendency to commodity gluts and surfeits of capital, and its thirst for superprofit from abroad, “Marxist economics” in the latter twentieth century has largely jettisoned the idea of contradictions and endogenous crises in capitalism. The result has been to understand capitalism as a promethean and self-sustaining system, an understanding which is closer to Schumpeter than Marx (Desai 2016a). Capitalism, thus understood, does not “need” imperialism, though it regrettably happens (Zarembka 2002, 8).

With the understanding of imperialism unhinged from capitalism’s dynamics and contradictions, it also became possible, in the same breath, to insist that postwar imperialism remained undiminished and, by some accounts, was even further strengthened, since the origins of capitalism. Such accounts cannot explain and must dismiss the significance of political and economic developments such as the Russian Revolution, decolonization, the Chinese Revolution, the Vietnamese victory, the Third World assertion of the 1960s and 1970s and the contemporary challenge of China and the other BRICS. It must also re-read the history of the failures of US and Western aggressions since the end of the Cold War as one of undiminished success and power. These accounts strike an increasingly false note as multipolarity is ever more widely acknowledged.

An alternative to these dead ends does exist which the authors of this introduction have, jointly and severally, been engaged in producing for over a decade (Desai 2013, 2015a, 2015b, 2016b; Freeman 2004; Kagarlitsky 2008, 2014; Kagarlitsky and Freeman 2004). However, this alternative needs to be disinterred from many layers of misunderstanding and mystification. In contrast with the widespread misreading of Lenin or Hilferding which portrays imperialism as product of a “monopoly” or “finance” stage of capitalism, Marx and Engels had clearly understood imperialism, including the British imperialism which grew so robustly in their time, as a systematic drive to territorial expansion in order to secure outlets for the gluts of capital and commodities to which capitalism was systemically prone. In the early twentieth century there was a burst of further theorizing about imperialism, but not because of the novelty of imperialism per se. Imperialism had already given Britain, the first capitalist industrializer, its vast empire. Rather, the new writings were prompted by a new development: growing competition for colonies as other powers industrialized and challenged Britain’s industrial and imperial primacy.

One can discern two distinct types of writing at this time. Luxemburg ([1913] 2003) and Hobson ([1902]1965) saw imperialism as a characteristic of capitalism per se, much as Marx and Engels had. On the other hand, Hilferding ([1910] 1981), Bukharin ([1917] 2003) and Lenin ([1916] 1970) focused on the new forms capitalism was taking with the onset of the second industrial revolution. Along with most commentators of the time, they distinguished capitalist imperialism from that of the old dynastic territorial empires such as the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman suzerainties, and related its heightened expansion to one of its key elements—industrial concentration (monopoly capital), high credit needs (finance capital) and increasingly close relations between the resulting big business and government (nationalization of capital) respectively.

While their analyses had the merit of identifying the new developments, they also ended up reinforcing the wrong impression that capitalist imperialism played no part in the mid-nineteenth century world (Gallagher and Robinson 1953). While undoubtedly capitalism was entering a new phase with the second industrial revolution, at the international level what was new was not that capitalism had become imperialist but that the “expansion of England,” largely uncontested by other imperial powers since the defeat of the French in Canada and India in the 1760s, was replaced by competition for colonies among the now several major industrial powers.

In retrospect 1870, when rival powers emerged to challenge Britain’s industrial and imperial supremacy, was the first multipolar moment. The challenges that it presented to Britain’s imperial expansion, accompanied by the competition it introduced in relations between imperial powers, established the limits of that expansion, culminating in the First World War and the Thirty Years’ Crisis that followed, initiating the first stage in the erosion of imperialism, which had reached not merely the high point of its power but the high point of its contradictions. These developments signalled the operation of the dialectic of uneven and combined development (UCD).

Just as capitalism’s contradictory and exploitative character creates new structures of class inequality within societies, it also creates new structures of international inequality between them. Just as class inequality gives rise to class struggles, so international inequality results in international struggle. It is not borne silently by its victims and their actions convert a condition—capitalism’s unevenness—into a dialectic in which while dominant countries seek to maintain the uneven configurations of world capitalism on which their dominance is grounded, contender states seek to challenge it by undertaking industrialization behind protectionist walls.

Dominant capitalist nations seek to confer special advantages on their capitalist classes, and to inflict the consequences of the contradictory development of capitalism within them, such as gluts of commodities and capital, on weaker states and territories over which they exercise formal or informal imperial control. While the former strive to maintain complementarity between their economies and those they are able to dominate, for example by relegating them to the status of markets for industrial products and suppliers of cheap raw materials or labour, the latter reject this role and instead seek similarity, particularly in terms of levels of industrial and technological development (Desai 2015c, 2015d). Such combined development, which may often fail, can take capitalist forms, as in the US, Germany and Japan in the late nineteenth century, or non-capitalist, “socialist” ones, as classically in the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China.

Though the term was coined, and the idea fully developed only much later by Trotsky in the first chapter of his History of the Russian Revolution (1934), an understanding of UCD was shared by other Bolsheviks of his generation and could be traced back to Marx and Engels (see Desai 2013, 36–43). Moreover, some version of it was also part of the thinking of intellectuals of contender countries—such as Alexander Hamilton of the US, Friedrich List of Germany or Pyotr Chaadaev and Count Witte of Russia—who proposed and implemented programmes of contender industrialization for their countries. The work of the Russian American economist Alexander Gerschenkron transferred UCD into the mainstream of US thinking in the form of “the advantages of backwardness” (Gerschenkron 1962; van der Linden 2012).

It is thanks to such state-directed and protectionist contender development, not free trade and free markets, that productive capacity has spread around the world. Contrary to free market and free trade discourses, states play a central role, not just in creating capitalist economies once for all, but in maintaining them and facilitating their productive expansion at every stage. Given this, the function of free market and free trade discourses is to subordinate other economies to imperial ones, reshaping the former

to complement the latter. Such discourses, including their twentieth century avatars —the discourses of US hegemony and globalization—are aimed by imperial countries towards those they dominate or wish to dominate to facilitate such subordination (Reinert 2007).

The success of attempts at combined or contender development is anything but guaranteed. They may fail, as in so many developing countries, or experience only limited success, as in Russia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Kagarlitsky 2008) or independent India but, as Chang (2002) has argued, none of the core capitalist countries has industrialized without it and as Amsden (2007) argued, without it, no development is possible in the developing world. Such contender development has operated since the beginnings of capitalism to weaken the structures of imperialism by spreading productive capacity despite attempts by dominant states to prevent its spread and, by increasing competition between industrialized states, it has also expanded opportunities for further contender development and spread of productive power. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, this spread of productive power has, if anything, accelerated.

Uneven and combined development since the Thirty Years’ Crisis The widespread acknowledgement of multipolarity in recent years enables us to cast fresh light on the evolution of the postwar world order. Though the US had sought to parlay its rising power into the sort of world dominance the UK had enjoyed before 1914 since the early twentieth century, the world had already become too resistant to this project. The US itself acknowledged this by scaling its ambitions down to making the dollar the world’s currency, specifically eschewing formal territorial empire. However, the already-too-multipolar world, and the internal economic contradictions inherent in this project, prevented even this lighter ambition from being realized, notwithstanding unceasing US attempts to impose it, bringing in their wake a trail of military, economic, political havoc extending indeed to the ideological sphere as US ideologies of its “hegemony” and “globalization” warped our understanding of the real evolution of the modern, capitalist, world order (Desai 2013).

Imperialism therefore emerged from its “Thirty Years’ Crisis” considerably weakened. As the existing balance of international power was upset and economic turmoil undermined the domestic legitimacy of many governments, the dialectic of uneven and combined development was intensified. The Russian and later Chinese revolutions at either end of that long crisis made a distinctive contribution to this. They added the socialist form to the historical inventory of forms of combined development and vastly expanded its toolkit (Hobsbawm 1994). They also put their political weight behind decolonization, which, by returning policy autonomy to the countries comprising the vast bulk of humanity, permitted them to pursue combined development. While this endeavour would be even harder for countries emerging from colonial subordination and distortion of their economies, the existence of the communist bloc did expand their options in terms of international economic and political linkages, breaking the monopoly of the advanced industrial world on advanced technology and finance, key ingredients for contender development, and often provided critical international support for Third World countries’ international initiatives.

Weakened though they were, imperial powers still sought (indeed were compelled by the contradictions of their own capitalisms) to perpetuate colonial relations of complementarity without formal colonial control in the postwar period, a dispensation critical writers dubbed “neocolonialism” (Nkrumah 1965). However, it is important to make some critical qualifications to this view, in order to counteract such prevailing misunderstandings as the idea that formal political independence meant little and that postwar

imperialism was simply the continuation, even intensification, of what had gone before.

First, it is true that decolonization did not guarantee that old complementarities would be replaced by new relations of similarity in short order, and nowhere did this actually occur. However, political independence and the policy autonomy that came with it usually had a significant effect. In the case of India, for example, the post-independence growth rate of “mere” 3.5%, long given the self-deprecating label “Hindu rate of growth,” was still 350% higher than the near zero growth rates of the colonial period (Nayyar 2006).

Second, while most focused on multinational corporations when identifying the economic structures through which such (neo) imperial domination was effected, they actually played a rather small and peripheral part. More important to understanding both the strengths and limitations of post-war imperial structures were two other things. On the one hand, all economies, those of the former colonizers and former colonies, became more national in the post-war period, and therefore more dependent on internally generated, and therefore, working people’s demand as the key stimulus to growth. In the First World, this redounded to the benefit of the working classes: compared to imperial times, when excess production had outlets in the colonies and working class consumption did not matter, working class consumption experienced a large one-time increase and economic growth became reliant on expanding it (Desai 2016a). In the Third World too, as both First World and other Third World countries protected their own markets, productive increases had to focus on domestic markets in the first instance. Secondly, therefore, if First and Third World per capita GDP diverged even more than they had diverged before, it was a function of the extent to which investments in higher technology production could be made in these economies (Mandel 1972).

In the post-war period, the recovery of Western Europe and Japan constituted the most important episode of contender development of the early postwar decades, undermining US dominance both within the imperialist bloc and in the world as a whole. Contrary to the assumption that conflicts between imperial powers were now a thing of the past, the US was forced to permit, and indeed, facilitate Western Europe’s contender development, thanks to the threat of communism; the “altruism” of its Marshall Plan really amounted to littlemore than a formof export financing aimed at keeping the war-swollen US economy growing, and constituted a small portion of the investment that powered European recovery.

At the same time, the existence of communist trade, technology and investment links determined that, while it was not spectacularly successful—as, say Japanese or German “miracle” recoveries were—development in the Third World had, by the 1970s, grown economically strong enough to begin narrowing the gap between their own and the First World’s economies and politically strong enough to demand a New International Economic Order which led to changes in key international arrangements such as GATT trade rules.

By the 1970s, the West had already entered its Long Downturn (Brenner 1998). It reopened the cleavages between Western powers, prompting European integration to accelerate (Mandel 1970). It also accelerated the Third World’s catch-up as the combination of slower investment in the West and the recycling of petrodollars through Western financial institutions, chiefly to the Third World, made practically free capital available to the Third World countries, many of which embarked upon ambitious heavy industrialization plans. The Brandt Report even recommended furthering this development to expand markets for the stagnant West (Independent Commission 1980) and lift it out of stagnation.

It would, however, become the now largely forgotten road not taken. Instead, amid the stagflation that afflicted Western economies, newly appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker choose to attack inflation rather than stagnation quite simply because doing the opposite would have entailed increases in the economic strength and political bargaining power of both domestic working classes and the Third World, endangering Western capitalist elites position in their own countries and in the world capitalist system.

While the resulting neoliberalism continues to impose a harsh regime of stagnant wages, high unemployment and a shrinking welfare state on Western working classes, and while it also visited two “lost decades” of development on most Third World countries, by 2000 it was already clear that the offensive would not lay the basis for any permanent reversal in favour of the capitalist classes of imperial countries. A growing number of Third World countries, with China at the forefront, had managed to avoid or resist sufficiently the neoliberal conditionalities of the West and its agents, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, and had continued, or resumed, their growth. At the same time, while the neoliberal strategy preserved the political primacy

of capitalists in the West, it did not revive productive growth. Instead, it promoted financial growth such that productive expansion only occurred as a result of the “wealth effects” of regularly inflated asset bubbles increasing consumption, particularly at the upper ends of the lengthening income spectrum (Desai 2016b).

The result was that, already by the end of the 1990s, it was clear to many that the world economy’s centre of gravity was shifting (O’Neill 2001) not just from one part of the imperial core to another but, for the first time in the history of capitalism, to parts of the formerly colonial or semi-colonial world. The 2008 financial crisis, the bursting of the mother of all asset bubbles of neoliberal financialization, further slowed Western growth down while leaving the BRICS and other emerging economies unaffected, further

accelerating this process.

How Not to Understand the Ukraine Crisis

With the Ukrainian civil war, the ongoing epochal transformation of the world order toward even greater multipolarity lurched forward mightily and understanding it requires us to understand this wider transformation. It cannot be understood as that of one “hegemony” to another: that understanding in all its forms, mainstream and left, did little more than give theoretical dignity to the ambitions of US policy-makers (Desai 2013, 124–41).

Rather it is one in which even the US lead in the size of its economy, on which its power rested, is now threatened as is Western pre-eminence generally. The previous such transition in the structuring of the international order, the Thirty Years’ Crisis (1914–45) of the nineteenth century imperial world, was a time of great military conflict, with two World Wars book ending it, and economic breakdown, with the Great Depression, which originated in the US, reverberating outwards to the farthest reaches of the world (Rothermund 1996). Last but not least, the long crisis also witnessed the destabilization of many a domestic order, with two revolutions, the Russian and Chinese, marking its beginning and end.

While many fear a repeat of such all-round mayhem, this fear remains inchoate chiefly because the contemporary discipline of international relations and its ruling paradigm, neo-realism, obscure, rather than illuminate, the real drivers of capitalist international relations (van der Pijl 2014). By positing more or less inevitable aggrandisement and conflict between powerful actors, not only do the neo-realists close off real inquiry into specifically capitalist drivers of conflict, they also facilitate the demonization of all leaders who challenge Western dominance as dictators—whether Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi

or, currently, Putin—irredeemably bent on expansionism and aggrandisement (which need not be explained) and authorizing Western actions against them.

The best such a discipline of international relations has been able to produce in terms of a deeper understanding of the confrontation of the status quo Western powers and rising and revived powers, pre-eminently China and Russia, is a reference to the “Thucydides Trap” (Allison 2012). The Greek historian had written of the long war between a rising Athens and the status quo power, Sparta, attributing it to the ambitions and fears aroused in both. The Chinese leadership has found it useful to invoke this metaphor in its practical diplomacy aimed at placating (though not submitting to) Western fear and hubris.

However its utility for understanding the contemporary transition in international relations is limited by at least two problems. First, it falls foul of Lenin’s important admonition not to confuse pre-capitalist and capitalist imperialism and thereby foreign relations: “Colonial policy and imperialism existed . . . even before capitalism. Rome, founded on slavery, pursued colonial policy and practiced imperialism. But “general” disquisitions on imperialism which ignore, or put into the background, the fundamental difference between socio-economic formations, inevitably turn into the most vapid banality or bragging, like the comparison: “Greater Role and Greater Britain.” (Lenin [1916] 1970, 731)

Second, it assumes that a mere increase in prosperity, and a concomitant relative increase in power in one country inevitably constitutes a threat to another. In any proper historical understanding of foreign relations, this cannot be assumed but must be explained in terms of the structure and dynamics of the social organization of production both of the powers concerned and those around them. Though the Western view places blame for the Thirty Years’ crisis on the “revisionist” power, Germany, and not on the inter-imperialist rivalries between capitalist imperialisms, more recent historiography (Clark 2012) has at least accepted a more even attribution of blame between the status quo and revisionist powers, more in keeping with the latter understanding while steering clear of its theoretical apparatus connecting imperialism and capitalism as does most scholarship.

The left’s understanding is, if anything, even more problematic. Before and during the Cold War, many parts of the left constituted the principal and indeed on many occasions the only internal critics of Western powers’ extra-territorial interventions though that of many others was muted by their hostility to Actually Existing Communisms. However, the post-Cold War era disoriented the left even more. Many left currents early on joined the mainstream of liberal opinion in the West in supporting US and Western war aims in the Gulf War of the early 1990s, the Western intervention in Yugoslavia on allegedly “humanitarian” grounds, not to mention the War on Terror.

In our own time, this continues with the support of many on the left for overthrow of Gadhafi and has continued its momentum with the widespread adhesion, among the Western left, to the proposition that Russia is the aggressor in Ukraine and, indeed an “imperialist” aggressor. This position dovetails nicely with the Western demonization of the Putin regime, not to mention with simplistic and ideological ideas of longer standing to the effect that Soviet foreign policy constituted a simple continuation of Czaarist imperialism. Many of these misunderstandings can be set right with a closer look at what followed the end of the Cold War in line with our narrative of the geopolitical economy of the capitalist world until then.

The surprises at the end of the Cold War The crisis in Ukraine fell on the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall and occurred in the space opened up by two major developments which, over that quarter century, belied the expectations the end of the Cold War aroused: that it would bring a “peace dividend” and that it would make the world unipolar under US leadership. Instead, the end of the Cold War was followed by a rising tide of Western confrontations against a series of greater and lesser forces that has crested in the confrontation with Russia over Ukraine. And, though it also forged North Atlantic unity anew and gave it a more substantial economic basis than had been possible earlier given the rather different “models” of capitalism in the Anglo-American and continental West European economies, this was not enough to provide a stable foundation for the US-dominated world.

The fact remained that the US’s victory in the Cold War had been largely pyrrhic. By the early 1990s, a decade of neoliberalism had failed to revive its productive economy and resulted only in an increasingly financialized pattern of weak growth. The increasing economic closeness between the Anglo-American and continental West European economies also rested on volatile foundations as Eurozone financial institutions were drawn into the maelstrom of dollar-denominated capital flows and asset bubbles. Such benefits as the Europeans derived from this brief financial dalliance soon proved costly as, outside the US, the costs of the 2008 financial crisis fell most heavily on the Eurozone, also laying the basis of its separate crisis two years later. These developments appear to have spelled the end of any easy assumption of North Atlantic unity in general and over Ukraine.

War levy in place of peace dividend

The post-Cold War confrontations of the West began with its liberal interventionism, tricked out in the language of human rights and democracy under the “globalization president” Bill Clinton, though they also served the purposes of the newly unified Germany eager to project its power eastwards. Their first achievement was the savage dismemberment of Yugoslavia to subordinate its constituent republics to US capitalism, particularly its financial demands, and give German corporations new avenues for investment. Its course was also determined by US and German manoeuvres over whether European security arrangements after German unification would remain compatible with US power (Gowan 1999). Though for the time being they were, the possibilities of US and European divergence after the end of the Communist threat would now never disappear.

Liberal interventionism was followed by the naked and unilateral militarism of the “empire president” President George W. Bush in Afghanistan and Iraq under the guise of the War on Terror. While many West European governments opposed this adventurism to a certain extent, in the European theatre they supported its corollary, the enlargement of NATO eastwards so EU enlargement could advance in its wake. The potential for US-German divergence was embedded here too.

While the US interest in NATO expansion lay in the further extension of its military reach and in the expansion of the captive clientele for its defence exports, all the more important given the general loss of competitiveness of much of US industry and its persistent trade deficits, for Germany it expanded the territories in which German forces could be deployed to precisely those where Germany might wish to deploy them. NATO and EU enlargement were rolled out over the next two decades eventually reaching Ukraine and triggering the present crisis (Nazemroaya 2012; Baldwin and Heartsong 2015).

The promised “peace dividend” never materialized simply because it could not have, not unless capitalism changed its stripes overnight. After all, the Cold War was never directed at communism alone; it was aimed at all countries that refused to “complement” the US and Western economies (Block 1977, 10) by assenting to and taking part in an economic division of the world’s labour which relegated them to a permanent state of economic dependency, confined to the supply of primary products, the cheaper manufactures and cheap labour. While communist countries were always, for the West, certainly the biggest offenders, the nationalist and developmentalist governments were never absent from them, as Mossadegh and Nasser found out, albeit with very different outcomes. Rather than accept such subordination and complementarity their only crime was that they had sought to develop similarity as the basis of a new equality.

After 1989, Eastern European economies in contrast proved amenable to accepting such complementarity under the guise of EU enlargement. It included subjection to the dreaded “shock therapy,” justified as necessary bitter medicine for the sins of the Soviet

past, and the present situation of “peripheral” subordination to the core of the EU in which these countries find themselves (Serfati 2016) Though many believed, not unreasonably, that NATO had lost its ColdWar raison d’etre after its end, it was not dissolved.

Instead, contrary to US promises to President Gorbachev when he wound up the Warsaw Pact and agreed to German unification that NATO would not move closer to Russia’s borders, it was enlarged precisely in that direction. The enlargement of NATO to include Poland was already on the Western Agenda as early as 1994 when the US and Germany sought to come to terms on Yugoslavia (Gowan 1999, 96). Poland was formally invited to join NATO in 1997 and joined, along with the Czech Republic and Hungary, in 1999. A second round of enlargement followed in 2004, which brought in Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. In 2008, NATO announced that Georgia and Ukraine were considered future members under the Eastern Partnership Initiative and the following year Albania and Croatia joined.

While EU and NATO enlargement integrated and subordinated East European economies to the US and, even more, to Germany more or less successfully, Russia proved another matter altogether. In the immediate post-Communist years, Yeltsin’s initial openness to the West and acceptance of “Shock Therapy” gave the appearance that Russia’s fate would soon match that of Eastern Europe. However, shock therapy exacted a terrible cost from Russia, casting it into an economic retrogression unprecedented in peacetime. According to the influential medical journal, The Lancet, under its impact, death rates rose so high and life expectancy sank so low that population fell by over 5 million over the next decade and a half (Stuckler, King, and McKee 2009). Naturally, these effects also destabilized Russia internally in ways even Yeltsin realized. Moreover, ongoing NATO enlargement in clear violation of US promises to Gorbachev also offended Yeltsin. Thus, already from the late 1990s on, the pattern of Western relations with Russia diverged radically from those with Eastern Europe, creating and shaping the space in which the Ukraine crisis would erupt.

The slide of the West into a new belligerent militarism has only been exacerbated as,since the 2008 financial crisis, even what remained of the US and the West’s control slips from their hands at an accelerating pace. This was not for want of effort: the unseemly haste of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee in handing Obama the Peace Prize in the first year of his Presidency notwithstanding, the Obama administration represented great continuities with its predecessor: same personnel, same aggression though, thanks inter alia to budget constraints, pursued through proxies, sanctions and with new and deadlier “hitech”weaponry such as drones. Indeed, and paradoxically for some, the very difficulties that the US and Western powers encounter in winning battles on the ground within the constraints of shrinking budgets has led to the expanding deployment of accident prone technological weapons in theatres where any accident may provoke a major conflagration.

There has been no let-up in the undisguised Western ambition of “making nuclear weapons an option” through the breakneck development—and deployment next to Russian borders—of anti-ABM technology, and research into battlefield nuclear weapons continues apace (CND 2006; Higgins 2007). Yet these measures have been even less effective. The key, indeed dominant, element in international turbulence around the world—whether in West Asia, North Africa, the South China Sea or in Europe itself—is the vain and shambolic but desperate effort by an increasingly disunited and incoherent West to retain control over events that it did not shape and indeed, in more and more cases, did not even foresee. These attempts are no less destructive for that: indeed, they are all the more dangerous to humanity for having a greater potential to spin out of control in unruly spirals of destruction. Certainly, both scholars and journalists were announcing the start of a New Cold War (Cohen 2009; Lucas [2008] 2014) between the US and China as well as Russia even more dangerous than the first, containing as it did an even greater possibility of a nuclear Third World War (Cohen 2014).

Multipolarity in Place of Unipolarity

US and Western triumphalism after the Cold War rested on shaky economic foundations. Over the previous decade neoliberal policies had failed to revive the productive economy and, instead, encouraged financialization. As these policies extended into the post-Cold War period, the US and UK, the two most neoliberal Western economies financialized rapidly. By the late 1990s they, and the system of dollar denominated international capital flows over which they presided, had managed to inflate the stock market bubble and, in the following decade, with critical European participation, they proceeded to inflate the “mother-of-all-financial-bubbles” in the form of the US housing and credit bubbles. It was attributed to a “Global Savings Glut” (in reality an alleged Asian savings glut) by Bernanke (2005) (for a critique see Chandrashekhar and Ghosh 2005) and George W. Bush parroted this attribution after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. In fact, however, the greatest external contribution to the bubble came from European financial institutions, preeminently German and French (Borio and Disyatat 2011; Nesvetailova and Palan 2008).

As the new century opened, with neoliberal policies unable to revitalize Western growth, the world’s centre of gravity had clearly begun moving away from the West and towards China and the other emerging economies and, since the crash of 2008, this trend has accelerated. Despite many problems, emerging economies have continued to grow robustly. The West’s financialization, and the reliance of its growth in the regular inflation of asset bubbles is both cause and consequence of its economic stagnation (Brenner 2009; Desai 2013; Freeman 2016). The political power of financial capital remains sufficiently great that even in the aftermath of the greatest of financial crises to have struck Western capitalism, the impulse to regulate finance has been weak at best and, as a consequence, the West remains mired in stagnation.

The 2008 crisis has likely also made the world more multipolar by destroying the economic basis on which the US and the EU, particularly between Germany and the Anglo- American world, had drawn closer in the post-Cold War period: European capital flows into the US credit bubble. Until German unification, France had managed to keep Germany within the distinctly more statist and welfarist continental model (van der Pijl, Holman, and Raviv 2011). Thereafter, however, with Germany’s increased weight within the EU, this proved more difficult and Germany’s post-unification turn, away from the productivist corporatism that kept its manufacturing sector so robust for so long and toward increasing neoliberalism and financialization, also received a great fillip from the launching of the Euro which opened new and (as we now know, only apparently) safe avenues for purely financial profit-making for German and French capital while accommodating persistent German export surpluses without any corresponding obligations such as fiscal transfers. It was this newly financialised European capital that became most heavily invested in the “toxic” securities generated by the US housing and credit bubbles of the early 2000s, not some putatively over-saving Asian capital (Borio and Disyatat 2011; Nesvetailova and Palan 2008) and they were also those who suffered most from it (Montalbano 2015; Serfati 2016).

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, national regulation of capital flows reasserted itself sufficiently strongly to ensure that while international capital flows did recover from their steep collapse, they remained about 60% short of their peaks (McKinsey 2013) and in Europe they are now more intra-European than trans-Atlantic. This outcome had already reduced the business of the British financial sector as the financial mediator between Europe and the US and the Brexit vote, whatever the final resolution, promised to reduce this role even further (Desai and Freeman 2016).

German unification also provided, in the absorption of East Germany, a “model” for subordinated absorption of former communist countries. German capital no longer needed the high degree of regulation and political compromise with labour that had hitherto characterized its highly productive economy. Eastward expansion, which promised to relieve German capital from these constraints, now triumphed over French advocacy of deepening within the EU. NATO enlargement behind which EU enlargement

advanced became the military counterpart to Germany’s closeness to the Anglo-American world and it put Europe too on a collision course with Russia. What is interesting, however, is that after the 2008 crisis destroyed the financial links between the Eurozone and the US and UK, only relatively minor Albania was added to NATO (though not to the EU), while the bid to bring Ukraine into the EU set off the slide into crisis and civil war.

The resumption of economic divergence between the EU’s largest economy and the Anglo-American economies is reinforced by the rather different military inclinations of the two sets of powers. Even in the case of Yugoslavia, where Germany had a great deal at stake, Germany showed little appetite for the USA’s confrontationist stance. Defeat in two world wars had taught Germany one thing very clearly: it cannot win a direct military confrontation with Russia. While it has successfully integrated most of Eastern Europe and while it seeks to penetrate Russia economically, and while the US stands ready to step into any power vacuum it creates, confrontation with Russia is inimical to the interests of both German capital and the German state.

Tensions between the more cautious approach of the European continent and the military adventurism of the US-UK were certainly apparent over Ukraine. On the one hand, Germany has now run up against the social and political limits of its disastrous stance on fiscal redistribution and its myopic, banker-led insistence on a strong Euro whatever the cost. It has become mired in multiple European crises—Greece and the more general revolt against neoliberalism in the EU, the migrant crisis, and Brexit to name the more prominent. These are certainly factors that call for caution. The twenty-first century is witness to a string of US and Western military failures—in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria, to mention the major ones—despite a resumption of high military expenditures, underlining the West’s inability to stall economic decline by military means.

On the other hand, however, the limits of the West’s declining diplomatic and military capacities are not always rationally assimilated by the West, for reasons that need to be spelled out and grasped. At least three factors are at work. The first of these is the independent role of the military-industrial complex, which has a vested interest in warfare since every rise in conflict creates greater opportunities for it both in terms of profit and in terms of political influence.

The second is the eruption of political crises within the EU, accompanied by the emergence of left-wing, anticapitalist forces as in Greece, Spain, Italy and of all places, Britain. These can no longer be contained and marginalized by the traditional parliamentary

mechanisms and offering concessions would require a break with austerity that would undermine what is left of the present malingering pattern of capitalist accumulation. In such situations, as the interwar history of Europe darkly demonstrates, the siren song of the fascisant right is a strong one because it can mobilize some of the same social forces as the left in support of continued capitalist dominance. But such forces, as the post-Maidan course of events in Ukraine starkly demonstrate, achieve this mobilization by recourse to the methods of physical force which are required of them to demonstrate their “real” commitment to the goals of racial superiority and national patriotism which motivate their supporters. Thus whilst such movements can on occasion take a protectionist and isolationist form, war is always a sure-fire way to capture their loyalty, a fact that is never lost on their puppet-masters.

Finally, and in contrast to all the rhetoric, not to say the misleading scholarship to the effect that the world order is dominated by a seamless hegemony, competition between capitalist states never disappears. Underneath NATO’s expansionism is a dangerous game of chicken in which the leading nations must demonstrate military “firmness” against the common threat so that the even greater threat that a rival capitalist power will step up to the plate and take their place at the centre of the action is averted. The result is that there are forces at work which require a continuation of military aggression irrespective of success.

Is Russia Imperialist?

This is the context in which the present confrontations between the West and certain emerging economies, particularly China and Russia, must be placed and in which the question of their alleged imperialism must be settled. Here we confine our remarks to Russia.

Post-communist Russia remains capitalist in a meaningful sense and as such, it is never impossible that the contradictions of its capitalism will lead the Russian state to seek resolutions for them both domestically and beyond its borders by using the means at its disposal, including its international power. However, both this consideration and its significance for the characterization of the Russian state must be qualified by a number of others.

First and foremost, as underlined by the contributions of Hudson and Sommers and Koltashev in this issue, Western allegations of Russian policy as the chief obstacle to Ukrainian sovereignty rest on ignoring the equal and indeed greater threat to this same sovereignty, not to mention its productive basis and material well being, that the EU represents. This contrasts with Ukraine’s economic links with Russia, which have formed the basis of its economy in recent decades.

Second, as we explained at the outset, the fundamental issue is that capitalist imperialism simply does not function as, and is not the same thing as, that which grounded the pre-capitalist and semi-capitalist empires of Europe and the Middle East in the nineteenth century. The conduct of modern Turkey can no more be understood as “neo-Ottoman” than Austria’s far right can be grasped as revitalized Habsburg expansionism. For the same reason, all attempts to cast Russia as some kind of reincarnation of Romanov imperial aspiration with Putin as a latter-day Ivan the Terrible are rooted in an ahistorical approach. As David Lane argues in his contribution to this issue, it is also one-sided in that the actions of far more powerful capitalist imperialisms of the Western powers are swept under the convenient carpet of human rights and democracy.

Third, after suffering the most dramatic decreases in material well-being of any population in peacetime under Yeltsin in the 1990s, the Putin regime’s legitimacy is reliant on providing stability and at least modest increases in living standards to Russians (Kagarlitsky in this issue; Sakwa 2014). Therefore, though popular interests have been subordinated to capitalist ones in many ways as they must be in capitalist countries—for example in the refusal to manage the capital account and instead to permit free capital flows which so regularly inflict currency devaluations—there is a limit to how far Putin can go. Given that the leading Russian capitalists’ overriding aim seems to be to slot their country into an assigned subordinate position in the world hierarchy of capitalist classes, subjecting its economy to ever-greater complementarity-induced dependency, this is just as well. And the requirements of domestic legitimacy also mean that the extent to which the Russian state can be used to impose its capitalists’ will on other territories and populations at the expense of the well being of Russians is also limited.

Further, as the world’s productive, and correspondingly its political, diplomatic and military capabilities, increase and spread, the ability of all powers to exert their will on others shrinks correspondingly, as even the West is discovering. Even when it comes to small countries not yet enjoying the fruits of this spread of productive power, the proliferation of productive, technological and financial capacity among other powers at least gives the former more options and possibilities for playing various trade and investment possibilities off against one another and obtaining better terms.

In this context two other facts become relevant. Even compared to a decliningWest, Russia’s capacity to undertake foreign adventurism is tiny. There is, firstly, the sheer military asymmetry between Russia on the one hand and the US and its allies on the other; it is vast. NATO’s 28 members operate military bases in 80 countries spanning the world from the South Atlantic to the North Pacific, while Russiamaintains military facilities,mostly nominal and defensive, in precisely 10 countries, the combined population ofwhich adds up to little more than its own, and of which all except two (Syria and Vietnam) share borders with it.

Moreover, as Table 1 shows, this disparity is not confined to the military sphere but is reinforced by economic disparity. Russia’s GDP is lower than Brazil or Italy or Canada, and barely bigger than Australia and Spain. Dzarasov in this issue, and in his extended work on the question (Dzarasov 2013) provides the clearest possible evidence for the conclusion that Russia’s transition from the Soviet system entailed a major loss of productive power and prosperity accompanied by attempts to subordinate the Russian economy— most strikingly evident in the role of its oil resources—making it “dependent” in the classical

sense of the word.

So, while Russian capitalists may well be inclined to use their state in order to project their power outwards, the ability of the Russian state to perform this role is constrained, to say the least, both by the large number of other powers of greater or equal economic weight, and by the pull which their capitalists exert in the heart of the Russian economy. These limitations are further explored by Buzgalin et al. in this issue.

To this point about economic size and power, we must add another. As Freeman (2004) shows, the GDP per capita of the world’s nations—the most fundamental measure of economic well-being—have long divided them into two very distinct groups of low and high income economies and, though this is now changing, the divide lingers. Even today, very few countries occupy the middle position and so far only four countries containing less than 2% of the world’s population—Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea and Taiwan—having moved from being low to being high income. This divide has long been buttressed by a world economic and military order, dominated by organizations like the IMF, the World Bank and NATO.

Finally, let us consider another measure, holdings of foreign capital. Russia and also China are even lower in the pecking order of this measure than in the rankings of military presence or income. With capital exports barely above Finland and well short of Norway, standing at one-twenty-fifth those of the US and one-thirteenth that of the UK (per capita, one fortieth), Russia has a long way to go to enter the select world league of imperialist robber-nations .

If the imperial order of Western supremacy is very slowly beginning to change, the reasons are instructive. China’s economic growth in recent decades is precisely the outcome of a consistent refusal to accommodate to the Washington Consensus; that is, a refusal to allow China’s economy to be shaped by the institutional structures that this system generated. Other emerging economies have also succeeded precisely to the extent that they have refused neoliberal policies. Russia’s “recovery”—a termthatmakes sense only in comparison with the disastrous years of Shock Therapy—arises from a reversal of the policies imposed in those years.

Thus, these economic successes, far from being the result of “globalization” (as the Western mainstream is wont to insist) and least of all from an accommodation to imperialist norms of conduct, arose precisely from a break from the strictures of the imperialists. To attribute them to a rise of a new imperialism is tantamount to asserting that freedom from slavery inevitably entails the attainment of the status of slave driver.

The imperialist powers are those that either themselves directly participate, militarily and economically, in the mechanisms that maintain the configurations of uneven development that favour them and seek to prevent contenders from breaking out of the relations of complementarity to imperial economies to attain similarity. Historically the stability of this system, dividing the world as Roy (1920) noted and the Communist International agreed into two great groups of dominant and dominated nations, is quite remarkable: the group of “robber baron” nations that Roy and Lenin identified has changed since 1914 only by the loss of Argentina and the incorporation of the “Newly Industrialised Countries,” together with a small European periphery. By the same token, less than 100 million people live in countries described by the same commentators as “colonial or semi-colonial” that have since finally left the ranks of the poor and dependent.

It is in this light that we have to understand the significance of the growing resistance to imperialism and its growing success despite setbacks. This is true as much for smaller and weaker countries such as Venezuela, Ecuador or Bolivia as for larger and economically quite significant countries such as the BRICS. One can never rule out the possibility that larger and more powerful of these capitalist contenders might seek to deploy their wealth and power in ways that subordinate lesser ones. However, their ability to do so is considerably more limited than that of the traditional imperial powers despite their decline. The power of the

emerging economies is further limited by the very expansion of productive capacity and power of which they are a part. And the demonstrable economic and military benefits are working together to reject complementarity and achieve similarity point in the opposite direction, as illustrated by the growing tendency towards Eurasian integration. It is arguably the one outcome of the present world conflict that ismost feared by the older powers, yet the one that is brought daily closer by their provocations.

For this plurality of relatively productive and prosperous countries gives weaker countries more options, as the West, for instance, is discovering in Africa. Moreover, that is why it does not work to brand contender nations breaking free, or striving to do so, from the imperial system as actual or nascent imperialists.

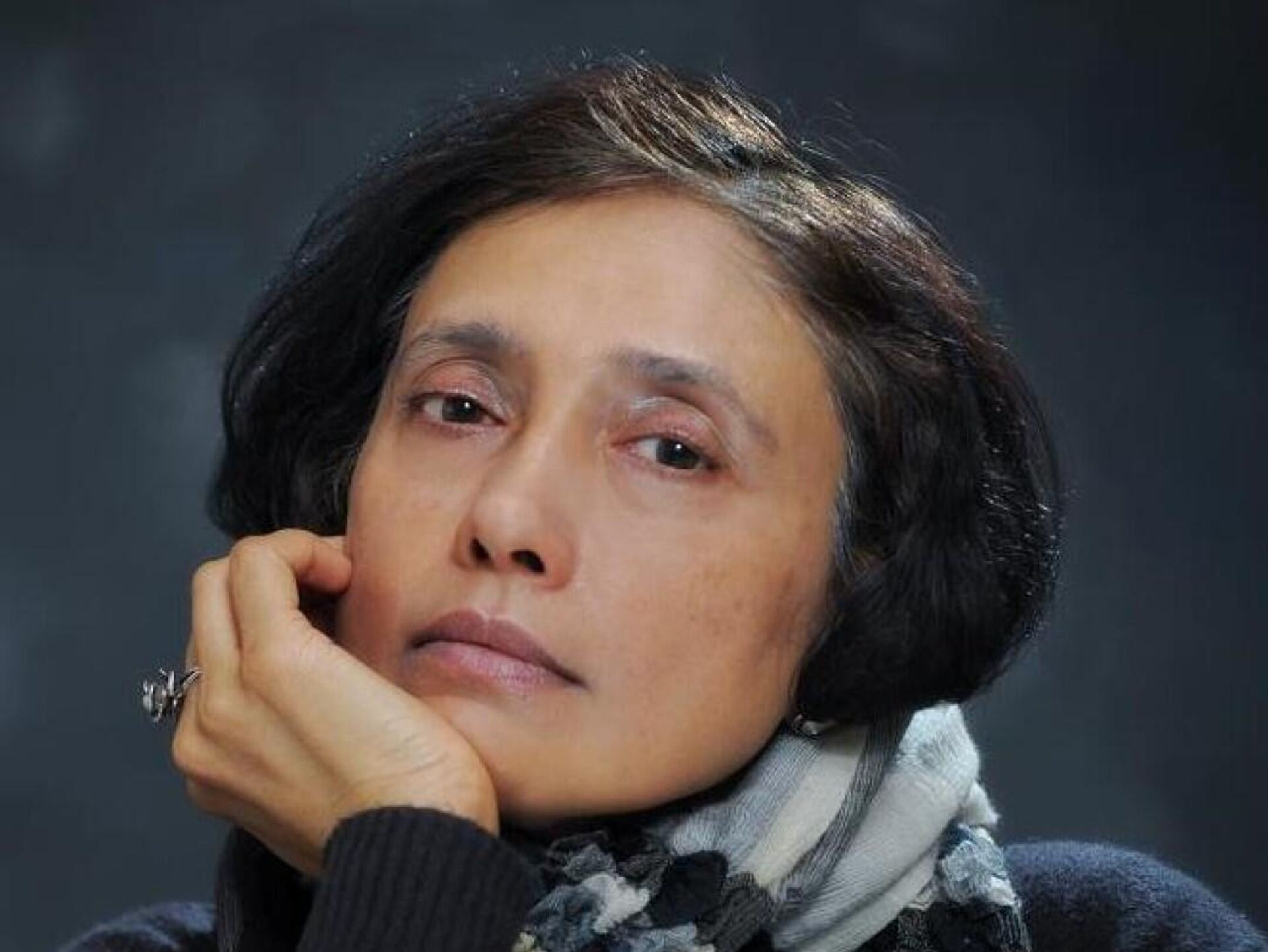

Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman & Boris Kagarlitsky

Radhika Desai, Alan Freeman & Boris Kagarlitsky (2016) The Conflict in Ukraine and Contemporary Imperialism, International Critical Thought, 6:4, 489-512, DOI: 10.1080/21598282.2016.1242338, To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21598282.2016.1242338