I wish to propose a general definition of empire that does not tie it with annexation and occupation of foreign territories and, therefore, is able to capture the new forms of indirect and informal control that have become common in recent decades. The imperial prerogative, I suggest, is the power to declare the colonial exception. Everyone agrees that nuclear proliferation is dangerous and should be stopped. But who decides that India may be allowed to have nuclear weapons, and also Israel, and may be even Pakistan, but not North Korea or Iran? We all know that there are many sources of international terrorism, but who decides that it is not Saudi Arabia or Pakistan but the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq that must be overthrown by force? Those who claim to decide on the exception are indeed arrogating to themselves the imperial prerogative. Keywords: empire, nation, colonialism, the Bandung conference

The New Nations

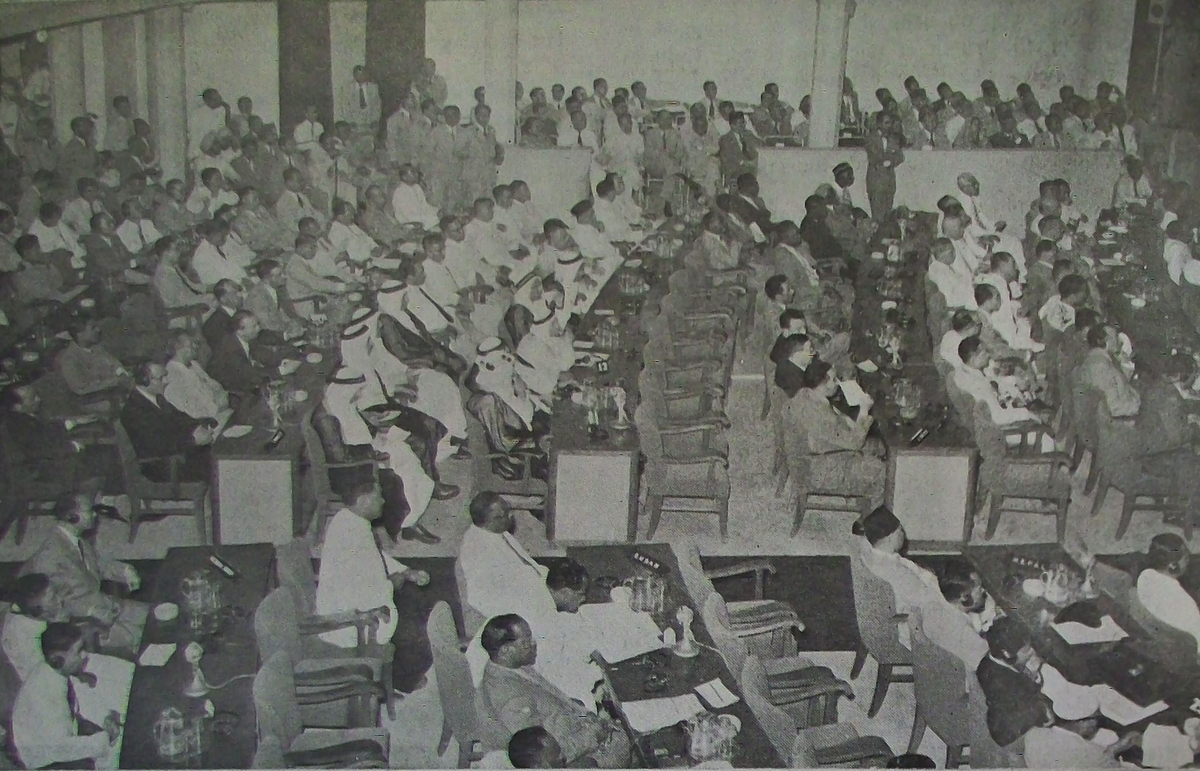

‘We are often told “Colonialism is dead.”Let us not be deceived or even soothed by that. I say to you, colonialism is not yet dead.’ Those were the words of President Achmed Sukarno of Indonesia 50 years ago at the opening of the Asian-African conference in Bandung. He went on to elaborate:

I beg of you, do not think of colonialism, only in the classic form which we of Indonesia, and our brothers in different parts of Asia and Africa, knew. Colonialism has also its modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control, actual physical control by a small but alien community within a nation. It is a skilful and determined enemy, and it appears in many guises. It does not give up its loot easily. Wherever, whenever and however it appears, colonialism is an evil thing, and one which must be eradicated from the earth. (Sukarno 1955: 23)

Do those words still have a ring of truth? Could they be said about the world today? I believe they can, even though in many crucial respects the world has changed rather drastically in the last half a century. Let me quickly recount some of the things that were said at the Bandung conference, attended by such leading lights of the Afro- Asian world as Chou En-lai, Jawaharlal Nehru, Ho Chi Minh, Kwame Nkrumah and Gamal Abdel Nasser. We should remember that, in 1955, most of the countries of Africa were still under British or French or Portuguese colonial rule. So, of the many things said at Bandung, let us see which are the ones that are still of relevance and which have gone into the trash folder of history.

On the economic side, the Bandung conference stressed the need for economic development of the countries of Asia and Africa. ‘Development’ was, of course, a concept that was very much in vogue 50 years ago, and along with it the idea of planned industrialization through the active intervention of the nation-state. The conference resolution shows that most countries in the region saw themselves mainly as exporters of primary commodities and importers of industrial products. The conference discussed the possibility of collective action to stabilize the international prices of primary commodities. This condition has largely changed, at least for the countries of Asia. While large pockets of subsistence agriculture and poverty still remain in many countries, the main economic dynamic is now a rapidly growing, principally capitalist, modern industrial manufacturing sector that is quite diversified in its products and use of technology and that supports the growth of modern financial, educational and other tertiary sectors. What must be emphasized, however, is that this transformation has been brought about everywhere in Asia, not only in China or India but also in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia or Indonesia, by the direct, systematic and active intervention of the postcolonial nation-state and its political leadership.

But the economy is also the one respect in which the historical trajectory in Asia seems to have diverged enormously in the last half a century from that in Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa today has become, in the popular media, synonymous with poverty, a blot on the conscience of the world, the last place where absolute poverty is not yet on the way to eradication. It is also the place where

the nation-state is said to have utterly failed in delivering the promises made at the time of its birth. For Africa, the cry now is for the rest of the world to deliver what the nationstate has failed to deliver. That is the obvious sub-text of the G-8 resolution at Edinburgh in July this year, pledging 50 billion dollars to end poverty in Africa. It is hardly insignificant that of the key players at Bandung 50 years ago, China and India were invitees this summer to the Gleneagles summit of the world’s most powerful economies. That is a dramatic measure of how much the world has changed since 1955. No one talks of an Afro-Asian economic world any more.

On the political side, the main discussions at the conference were on the subject of human rights. It is particularly interesting to re-read these discussions today because they show how radically the context as well as the framework of debate on this subject has changed. In 1955 at Bandung, no one had any doubt about the principal problem of human rights in the world: it was the continued existence of colonialism and racial discrimination. There was little doubt either about the chief instrument by which human rights were to be established: it was the principle of self-determination of peoples and nations. That was the principle the United Nations had enshrined. The leaders assembled at Bandung declared that the UN charter and declarations had created ‘a common standard of achievement for all peoples and nations’ (Appadorai 1955: 8). Accordingly, the conference supported the rights of the Arab people of Palestine. It called for the end to racial segregation and discrimination in Africa. It supported the rights of the peoples of Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia to self-determination. It called for the admission to the United Nations of Japan, Ceylon, Nepal, Jordan, Libya, Laos, Cambodia and a united Vietnam.

Further, the Bandung conference reaffirmed the five principles of promotion of world peace, namely, mutual respect of all nations for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Amplifying on these principles, the conference affirmed the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, but warned that arrangements for collective defence must not be used to serve the particular interests of the big powers. The leaders at Bandung thought that they could, as President Sukarno said, ‘inject the voice of reason into world affairs’.

Sukarno himself mentioned the role of some of the Prime Ministers of Asian countries in ending the war over continued French occupation of Indo-China. ‘It was no small victory and no negligible precedent,’ he said. ‘The five Prime Ministers did not make threats. They issued no ultimatum, they mobilized no troops. … They had no axe of power-politics to grind. They had but one interest – how to end the fighting [in Indo- China]’ (Sukarno 1955: 19–29). The President did not know at the time, of course, that he had spoken too soon: the war in Indo-China would, before long, resume and take a tortuous and brutal course over the next two decades.

Looking back, it seems clear that this was the time, in the two decades following the end of World War II, that the nationstate was established as the normal form of the state everywhere in the world. The normative idea was unequivocally endorsed in the principle of self-determination of peoples and nations. The fact that the norm had not been fully realized was pointed out as a shortcoming, something that had to be overcome. It presented to the peoples of Asian and African countries an object of struggle, a goal that had complete moral legitimacy. It also provided a criterion for identifying the enemy: The enemy was colonialism, the practices of racial superiority and the lingering fantasies of world domination by the old imperial powers.

A Post-National Age?

How are things different today? There are still a few places where ‘national liberation’ remains an emotive object of political struggle. Perhaps the most intractable as well as the most justified of such national struggles has been that of the Palestinian people, but the reason why Palestinians do not yet have a state of their own is not because the principle of national self-determination is difficult to apply to their case but because every suggested solution has been blocked by one or the other big powers having crucial strategic interests in the region. In this sense, the Palestinian case is somewhat unique. But the Kashmir question too has remained unresolved for more than 50 years. There is the question of the Kurds, a people whose claims as a nationality have, once again for unique reasons of colonial history, never been sufficiently recognized in the international arena.

There has been a lot of bloodshed and bitterness in many of the regions of the former Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia over contending ‘national’ claims. Such identities and claims had been successfully contained for several decades within a complex, and authoritarian, federal structure of socialist government. With the collapse of the socialist regimes, the container appears to have shattered into pieces. But all of these examples of unresolved claims of national selfdetermination can be understood as remnants of an older order of nation-state normativity that had become universal in the second half of the twentieth century.

The new order, it is being claimed, seeks to go beyond the framework of nationstates. It attempts to preserve the achievements of the nation-state while overcoming its frequently disastrous shortcomings. These arguments are coming from different ideological positions and there is not yet a coherent body of theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence that can be pointed out as the definitive description of this new order. However, some of these arguments have come from very distinguished thinkers and scholars, mostly from Europe. Let me point out what I think are the significant features of this corpus of arguments.

First of all, there is a general recognition that significant changes occurred in the structure of capitalist production and exchange in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The most common name for this phenomenon is globalization. Superficially, this refers to the huge increases in international trade and flows of capital, in the movement of people across national borders and in the spread of information and images enabled by the new communications technology. It has been pointed out, of course, that as far as trade, export of capital and migration are concerned, the two decades before World War I saw an equal if not higher degree of globalization. But the period from the 1920s to the 1970s, which is the period of consolidation of both the nation-state and the modern national economy, clearly produced a worldwide grid of economic activities defined over nationstates. Compared with the middle decades of the twentieth century, therefore, the changes in the last two decades were dramatic.

Those who have looked at globalization more carefully, however, point out that what changed decisively in the last two decades of the twentieth century was the emergence of a new mode of flexible production and accumulation and the rapid expansion of the international financial market. New developments in communications technology allowed for innovations in the management of production that could now disperse different components of the production process away from the centralized factory to smaller production and service units often located in different parts of the world and sometimes even in the informal household sector.

Alongside, there was a huge rise in the speculative investment of capital in the international markets for stocks, bonds and currencies. These two developments have jointly provided the basic economic push away from the old model of national economic autarchy to one where global networks are acknowledged as exercising considerable power over national economies.

It is against this background that leading thinkers of Europe have been arguing for some time for a relaxation, if not a dismantling, of the old structure of national sovereignty that, as we said, had become normative in the middle of the twentieth century and was identified by the leaders at Bandung as the unfinished agenda of the worldwide anti-colonial struggle. Many of these proposals have been driven by the experience of a successful integration of several European states, with long histories of antagonism, into a single European Union. There are now virtually no national controls over trade, travel and employment across national borders within Europe. There are numerous ways in which the sovereign powers of the nation-state have been curtailed in the fields of law, administration, taxation and the judicial system. There is now a single European currency. More significantly, it has been argued that the relaxation of sovereign controls at the top has also facilitated the devolution of powers below the level of the nation-state. In Britain, for instance, Scotland and Wales now have their own parliaments, an idea that would have been regarded as hugely threatening even 30 years ago.

It is not only sovereignty – the new post-national theorists have argued that notions of citizenship are also undergoing radical change. The idea that the nationstate is the only true home of the citizen, the only guarantor of his or her rights and the only legitimate object of his or her loyalty is changing fast and, say these theorists, should change even more quickly. If we can take the idea of citizenship away from the exclusive domain of the nation-state and distribute it among different kinds of political affiliations, then we would have more effective and democratic means to deal with problems such as the rights of migrants, the rights of minorities, cultural diversity within the nation and the freedom of the individual. There will be little need for separatism, terror and civil war. It is in this spirit that Jurgen Habermas has spoken of the ‘post-national constellation’ and David Held and Daniele Archibugi of ‘cosmopolitan democracy’.

Empire Today

If this is the passage of the idea of the nation-state in the last half of the twentieth century, how has the idea of empire fared in the same period? Imperialism of the old kind mentioned by President Sukarno in his speech at Bandung did come to an end by the 1960s. The transition was not peaceful everywhere. When the French and the Dutch reoccupied their colonies in Southeast Asia after the defeat of Japan in World War II, they were met by armed popular resistance. The Dutch soon gave up Indonesia. In Indochina, the French withdrew in the mid-1950s, but of course the region was soon engulfed in another kind of conflict. The nationalist armed resistance became victorious in Algeria in the early 1960s.

In the British colonies, the transfer of power to nationalist governments was generally more peaceful and constitutionally tidy. It is said that this was because the liberal democratic tradition of politics in Britain ultimately made it impossible for the nation to sustain the anomaly of a despotic colonial empire and to resist the moral claim to national self-government by the colonized people. By acquiescing in a process of decolonization, it was asserted, British liberal democracy redeemed itself. The claim has been recently celebrated once more by Niall Ferguson in his Empire, intended as a manual of historical instruction for aspiring American imperialists (Ferguson 2002).

Of course, alongside the question of the moral incompatibility of democracy and empire, another argument had also come to dominate discussions on colonialism in the middle of the twentieth century. This was the utilitarian argument which claimed that the economic benefits derived from colonies were far outweighed by the costs of holding them in subjection. By giving up the responsibility of governing its overseas colonies, a country like Britain could secure the same benefits at a much lower cost by negotiating suitable economic agreements with the newly independent countries. However, not every section of ruling opinion in Britain took such a bland cost-benefit view of something so sublime and noble as the British imperial tradition. Conservative governments in the 1950s were hardly keen to give up the African colonies, and when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956, Britain and France decided to intervene with military force. It was American pressure that finally compelled them to pull back. By then, it had become clear that the future of British industry and trade was wholly dependent on the protective cover extended by the US dollar. The decolonization of Africa in the 1960s effectively meant the end of Britain as an imperial power. The costbenefit argument won out, leaving the moral reputation of liberal democracy largely in the clear (Louis and Robinson 1993).

The United Nations, as it emerged in the decades following World War II, was testimony to the historical process of decolonization and the universal recognition of the right of self-determination of nations. It was living proof of the universal incompatibility of democracy and empire.

The declared American position in the twentieth century was explicitly against the idea of colonial empires. The imperialist fantasies of Theodore Roosevelt at the beginning of the century soon turned into the stuff of cartoons and comic strips. Rather, it was an American president, Woodrow Wilson, who enshrined the principle of self-determination of nations within the framework of the League of Nations. After World War II, US involvement in supporting or toppling governments in other parts of the world was justified almost entirely by the logic and rhetoric of the Cold War, not those of colonialism. If there were allegations of US imperialism, they were seen to be qualitatively different from old-fashioned colonial exploitation: this was a neo-imperialism without colonies.

In fact, it could be said that through the twentieth century, the process of economic and strategic control over foreign territories and productive resources was transformed from the old forms of conquest and occupation to the new ones of informal power exercised through diplomatic influence, economic incentives and treaty obligations. A debate that was always part of the nineteenth- century discourse of imperialism – direct rule or informal control – was decisively resolved in favour of the latter option.

Has globalization at the end of the twentieth century changed the conditions of that choice? The celebratory literature on globalization in the 1990s argued that the removal of trade barriers imposed by national governments, greater mobility of people and the cultural impact of global information flows would make for conditions in which there would be a general desire all over the world for democratic forms of government and greater democratic values in social life. Free markets were expected to promote ‘free societies’. It was assumed, therefore, as an extension of the fundamental liberal idea, that in spite of differences in economic and military power, there would be respect for the autonomy of governments and peoples around the world precisely because everyone was committed to the free and unrestricted flow of capital, goods, peoples and ideas. Colonies and empires were clearly antithetical to this liberal ideal of the globalized world.

However, there was a second line of argument that was also an important part of the globalization literature of the 1990s. This argument insisted that because of the new global conditions, it was not only possible but also necessary for the international community to use its power to protect human rights and promote democratic values in countries under despotic and authoritarian rule. There could be no absolute protection afforded by the principle of national sovereignty to tyrannical regimes. Of course, the international community had to act through a legitimate international body such as the United Nations. Since this would imply a democratic consensus among the nations of the world (or at least a large number of them), international humanitarian intervention of this kind to protect human rights or prevent violence and oppression would not be imperial or colonial.

The two lines of argument, both advanced within the discourse of liberal globalization, implied a contradiction. At one extreme, one could argue that democratic norms in international affairs meant that national sovereignty was inviolable except when there was a clear international consensus in favour of humanitarian intervention; anything less would be akin to imperialist meddling. At the other extreme, the argument might be that globalization had made national sovereignty an outdated concept. The requirements of peace-keeping now made it necessary for there to be something like an Empire without a sovereign metropolitan centre: a virtual Empire representing an immanent global sovereignty. There would be no more wars, only police action. This is the argument presented eloquently, if unpersuasively, by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (Hardt and Negri 2000).

What is New about Empire?

Since Hardt and Negri’s analysis provides some ingenious and influential arguments about the place of Empire in the globalized world of the 21st century, let me briefly review their proposal before moving on to my own assessment of the situation today.

Hardt and Negri speak of two logics of sovereignty within the modern political imagination. One is the transcendent sovereignty of the nation-state, demarcated over territory, located either in a sovereign monarchical power (à la Hobbes) or a sovereign people (à la Rousseau). Its logic is exclusive, defining itself as identical to the people that constitutes a particular nationstate as distinct from other nation-states. Its dynamic is frequently expansionist, leading to territorial acquisitions and rule over other peoples that are known in modern world history as imperialism. The second logic is that of the immanent sovereignty of the democratic republic, located, they argue, in the constituent power of the multitude (as distinct from the people) working through a network of self-governing institutions embodying multiple mechanisms of powers and counter-powers. The logic of immanent sovereignty is inclusive rather than exclusive. Even when territorialized, it sees its domain as marked by open frontiers. Its dynamic tendency is towards a constantly productive expansiveness rather the expansionist conquest of other lands and peoples. Germinating in the republican ideals of the US constitution, the logic of immanent sovereignty now points towards the global democratic network of Empire (Hardt and Negri 2000).

It is necessary to point out that even in their description of the historical evolution of the United States as an immanent Empire, Hardt and Negri acknowledge that there were closed and exclusive boundaries. First of all, it was possible to conceive of the expansive open frontier only by erasing the presence there of Native Americans who could not be imagined as being part of the supposedly inclusive category of the constituent multitude. That was the first inflexible border. Second, there were the African-

Americans who were, as Hardt and Negri point out, counted as unequal parts of the state population for purposes of calculating the state’s share of seats in the House of Representatives but, of course, not given the rights of citizens until the late twentieth century. The latter became possible not by the operation of an open frontier expanding outwards but rather by the gradual loosening of an internal border through a pedagogical, and indeed redemptive, project of civilizing, i.e. making citizens.1 Hence, even in the paradigmatic case of the United States as an immanent Empire, there was always a notion of an outside that could not be wishfully

imagined as an ever-receptive open space that would simply yield to the expansive thrust of civilization. This outside consisted of practices (or cultures) that were resistant to the expansion of Empire and thus had to be conquered and colonized. As with all historical empires, there are only two ways in which the civilizing imperial force can operate: a pedagogy of violence and a pedagogy of culture.

From this perspective, one has to see the US myth of the melting pot as not one of hybridization at all, as Hardt and Negri would have it, but rather as a pedagogical project of homogenization into a new, internally hierarchized, and perhaps frequently changing, normative American culture. In this respect, the US empire is no different from other empires of the modern era for whom contact with colonized peoples meant a constant danger of corruption: an exposure to alien ways that could travel back and destroy the internal moral coherence of national life. Hence, the pedagogical aspect of civilizing has only worked in one direction in the modern era – educating the colonized into the status of modern citizens; never the other way, as in many ancient empires, of conquerors allowing themselves to be civilized by their subjects. It is hard to see any evidence that the US empire is an exception to this modern rule. Hardt and Negri also make the argument that since the new Empire is immanent and inclusive, and its sovereignty de-territorialized and without a centre, the forms of anti-imperialist politics that had proved so effective in the days of national liberation and decolonization have become obsolete. Anti-imperialist nationalism, grounded in the transcendent reification of the sovereign people as actualized in the nation-state, can now only stand in the way of the global multitude poised to liberate itself in the ever-inclusive, hybrid and intrinsically democratic networks of Empire (Hardt and Negri 2000).

Most readers have found this to be perhaps the least persuasive argument in Empire. But the point that needs to be made here is that although the transcendent and territorialized idea of sovereignty located in an actual people-nation is a predominant performative mode in most third-world nationalisms, the immanent idea of a constituent power giving to itself the appropriate machineries of self-government is never entirely absent. Indeed, just as the ‘people’ can be invoked to legitimize exclusive, and often utterly repressive, national identities held in place by nation-state structures, so can it be invoked to critique, destabilize and sometimes to overthrow those structures. One might even say that the relative lack of stable institutionalization of modern state structures in postcolonial countries – a matter of persistent regret in the political development literature – is actually a sign of the vital presence of this immanent notion of a constituent power that has still not been subdued into the banal routine of everyday governmentality.

Think of an entire generation of Bengalis who went, from the 1930s to the 1970s, imagining themselves first as part of an anticolonial Indian nationalism, then as part of a religion-based Pakistani nationalism, and finally as a language-based Bangladeshi nationalism, reinventing itself every time as a new territorial nation-state and yet, surely, remaining, in some enduring sense, the ame constituent power giving itself the institutions of self-rule. If immanence and transcendence are two modes of sovereign power in the modern world, it is hard to see in what way the US constitution has a monopoly over them.

I do not think, therefore, that the new globalized networks of production, exchange and cultural flows have produced, as Hardt and Negri claim, the conditions of possibility for a new immanent, de-territorialized and centre-less Empire. I do not find this argument persuasive even for the period of the 1990s – from the first Persian Gulf war to the war over Kosovo, when there was a relatively high level of consensus in the socalled international community for armed interventions to enforce international law and protect human rights. In the period after the invasion of Iraq, the argument has lost all credibility. Despite the rhetoric of a so-called global war against terror, the policies of the Bush administration and those of each of its allies seem perfectly explicable in terms of fairly old-fashioned calculations of ensuring national security and furthering national interests. Much of the resistance to US unilateralism, taking numerous forms from the diplomatic to the insurgent and cutting across ideological divides, has also taken the old forms of protecting the sovereign sphere of the national power. The question we must ask, then, is: how are we to understand the relation between nation and empire today? If nations and empires were declared to be incompatible 50 years ago at Bandung, has that assessment changed?

Empire is Immanent in the Modern Nation

It is true that the era of globalization has seen the undermining of national sovereignty in crucial areas of foreign trade, property and contract laws and technologies of governance. There is overwhelming pressure towards uniformity of regulations and procedures in these areas, overseen, needless to say, by the major economic powers through new international economic institutions. Can one presume a convergence of interests and a consensus of views among those powers? Or could there be competition and conflict in a situation where international interventions of various kinds on the lesser powers are both common and legitimate? One significant line of potential conflict has already emerged: that between the dollar and the euro economic regions. A second zone of potential conflict s over the control of strategic resources uch as oil.

A third may be emerging over the spectacular surge of the Chinese economy that could soon make it a potential global rival of the Western powers. These were the kinds of competitive metropolitan interests that had led to imperialist annexations and conflicts in the nineteenth century. That was the first period of capitalist globalization that ultimately led to World War I. Are we seeing a similar attempt now to stake out territories of exclusive control and spheres of influence? Is this the hidden significance of the differences among the major powers over the Anglo-American occupation of Iraq? Can this be the reason why the US political establishment has veered from the multilateral, globalizing, neo-liberalism of the Clinton period to the unilateral, ultra-nationalist, neo-conservatism of the Bush regime (Harvey 2003)?2

If there is a more material substratum of conflicts of interest in the globalized world at the beginning of the 21st century, then it

becomes possible to talk of the cynical deployment of moral arguments to justify imperialist actions that are actually guided by other motivations. This is a familiar aspect of nineteenth-century imperial history. It was in the context of an increasingly assertive parliamentary and public opinion, demanding accountability in the activities of the government in foreign affairs, especially those that required the expenditure of public money and troops, that the foreign and colonial policies of European imperial powers became suffused with a public rhetoric of high morality and civilizing virtues. And it was as an integral part of the same process that a ‘realist’ theory of raison d’état emerged in the field of foreign affairs, as a specialist discourse used by diplomats and policy-makers, that would seek to insulate a domain of hard-headed pursuit of national self-interest, backed by military and economic power, from the mushy, even if elevated, sentimentalism of the public rhetoric of moral virtue. This was the origin of ideological ‘spin’ in foreign and colonial affairs – a specific set of techniques for the production of democratic consent in favour of realist and largely secretive decisions made in the pursuit of the so-called national interest by a small group of policymakers.

But why should such duplicitous arguments be at all credible in a world where the form of the nation-state has become normative and universal? After all, nation-states have equal rights under international law and each has one vote in the General Assembly of the United Nations. Curiously, it is the very form of the universal equality of nation-states that has provided the common measure for comparing them according to various criteria. Thus, we are all familiar today with the statistical comparison of nations by indices such as the gross national product, economic growth, human development, quality of life, levels of corruption, and what have you. These are statistical measures of differences between nations. But statistical measures create norms and allow for the attribution of qualitative meanings and even moral judgements.

Thus, a norm may represent an average value of the empirical distribution of, let us say, literacy or infant mortality among the nations of the world. But a norm may also represent a certain desirable standard that is set as a target to be achieved. This allows for certain moral judgements to be made about the capacity, willingness and actual performance of nations in relation to such ethical standards. It is not surprising, therefore, that many of these judgements become judgements about culture. Necessarily, therefore, the normalization of the nation-state as the universal form of the political organization of humanity contains within itself a mechanism for measuring cultural difference and for attributing moral significance to those differences. I must add that the process of normalization also allows one to track differences over time, so that nations that did badly before could be seen to be improving, just as others could be seen to be slipping behind.

I think it can be demonstrated that the history of the normalization of the modern nation-state is inseparable from the history of modern empires. It was in the course of the worldwide spread of the European empires that virtually all of the forms and techniques of modern governance were developed, transported and adapted – notjust in one direction, i.e. from Europe to elsewhere, but also in the reverse direction, i.e. from the colonies to the metropolis. But it was also as part of the same process of the normalization of the nation-state that the rule of colonial difference was invented. Even as the universal validity of the norms

of modern governance was asserted, the rule of colonial difference allowed for the colony to be declared, on grounds of cultural difference, as an exception to the universal norm. Thus, even as the deputies of the revolutionary National Assembly in France declared the universal validity of the rights of man, they could announce at the same time that the rebellious slaves of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) did not have those rights. John Stuart Mill, in the middle of the nineteenth century, could write a whole book expounding the universal superiority of representative government, but not without inserting a chapter explaining why Indians and the Irish were not ready for it. One could easily fill an encyclopaedia with examples of the application of the rule of colonial difference in the last 200 years.

I wish to propose a general definition of empire that does not tie it with annexation and occupation of foreign territories and, therefore, is able to capture the new forms of indirect and informal control that have become common in recent decades. The imperial prerogative, I suggest, is the power to declare the colonial exception. Everyone agrees that nuclear proliferation is dangerous and should be stopped. But who decides that India may be allowed to have nuclear weapons, and also Israel, and may be even Pakistan, but not North Korea or ran? We all know that there are many sources of international terrorism, but who decides that it is not Saudi Arabia or Pakistan but the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq that must be overthrown by force? Those who claim to decide on the exception are indeed arrogating to themselves the imperial prerogative.

Declaring an exception, within the framework of normalization, immediately opens up a pedagogical project. The imperial power must then take on the responsibility of educating, disciplining and training the colony in order to bring it up to the norm. There have been in history only two forms of imperial pedagogy – a pedagogy of violence and a pedagogy of culture. The colony must either be disciplined by force or educated (‘civilized’) by culture. We have seen both of these forms in recent times, long after the era of decolonization and Bandung. Talking of Bandung and what it might mean to us today, I wish to end with one more quote from President Sukarno at the 1955 conference. ‘We are living in a world of fear,’ he said. ‘The life of man today is corroded and made bitter by fear. Fear of the future, fear of the hydrogen bomb, fear of ideologies. Perhaps this fear is a greater danger than the danger itself, because it is fear which drives men to act foolishly, to act thoughtlessly, to act dangerously’ (Sukarno 1955: 19–29).

It is not clear from his speech who specifically the President thought might act foolishly out of fear. But speaking of our situation today, we hear daily of angry men from ordinary backgrounds with little power who choose to act dangerously out of fear and resentment. But we often forget how much more thoughtless and dangerous people in power can be when, driven by fear, they choose to arrogate to themselves the prerogative of declaring the exception. The nation-state may not be at its healthy best any more, but empire is certainly not dead.

Partha Chatterjee (2005) Empire and nation revisited: 50 years after Bandung, Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 6:4, 487-496, DOI: 10.1080/14649370500316752 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649370500316752

References

Appadorai A. (1955) The Bandung Conference, New Delhi: Indian Council of World Affairs.

Asad, Talal (2003) Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Ferguson, Niall (2002) Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, New York: Basic Books.

Hardt, Michael and Negri, Antonio (2000) Empire, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, David (2003) The New Imperialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Louis, Wm. Roger and Robinson, Ronald (1993) ‘The imperialism of decolonization’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 22(3): 462-511.

Sukarno, Achmed (1955) Africa-Asia Speaks from Bandong, Djakarta: Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Partha Chatterjee, founding member of the Subaltern Studies editorial collective, is director of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, and visiting professor of anthropology at Columbia University. Professor Chatterjee’s books include The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World (Columbia University Press, 2004); A Princely Impostor? The Strange and Universal History of the Kumar of Bhawal (Princeton University Press, 2002); Partha Chatterjee Omnibus (Oxford University Press, 1999); A Possible India: Essays in Political Criticism (Oxford University Press, 1997);

The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories (Princeton University Press, 1993) and Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse? (Zed Books, 1986).