The World in which we are now living, the modern world-system, had its origins in the sixteenth century. This world-system was then located in only a part of the globe, primarily in parts of Europe and the Americas. It expanded over time to cover the whole globe. It is and has always been a world-economy. It is and has always been a capitalist world-economy. We should begin by explaining what these two terms, world-economy and capitalism, denote. It will then be easier to appreciate the historical contours of the modern world-system -its origins, its geography, its temporal development, and its contemporary structural crisis.

What we mean by a world-economy (Braudel’s economie -monde) is a large geographic zone within which there is a division of labor and hence significant internal exchange of basic or essential goods as well as flows of capital and labor. A defining fe ature of a world-economy is that it is not bounded by a unitary political structure. Rather, there are many political units inside the world-economy, loosely tied together in our modern worldsyst em in an interstate system. And a world-economy contains many cultures and groups-practicing many religions, speaking many languages, differi ng in their everyday patterns. This does not mean that they do not evolve so me common cultural patterns, what we shall be calling a geoculture. It does mean that neither political nor cultural homogeneity is to be expected or fo und in a world-economy. What unifies the structure most is the divisio n of labor which is constituted within it.

Capitalism is not the mere existence of persons or firms producing for sale on the market with the intention of obtaining a profit. Such persons or firms have existed for thousands of yean all across the world. Nor is the existence of persons working for wages sufftient as a d efinition. Wage-labor has also been known for thousands of yean. We are in a capitalist system only when the system gives priority to the endless accumulation of capital. Using such a definition, only the modern world-system h a s been a capitalist system. Endless accumulation is a quite simph concept: i t means that people and firms are accumulating capital in order to accumulate still more capital, a process that is continual and endless. I f we say that a system “gives priority” to such endless accumulation, it means that there exist structural mechanisms by which those who act with other motivations are penalized in some way, and are eventually eliminated from the social scene, whereas those who act with the appropriate motivations are revarded and, if successful, enriched.

A world-economy and a capitalist system go together. Since worldeconomies lack the unifying cement of an overall political structure or a homogeneous culture, what holds them together is the efficacy of the division of labor. And this efficacy is a function o f the constantly expanding wealth that a capitalist system provides. Until modern times, the worldeconomies that had been constructed either fell apart or were transformed manu militari into world-empires. Historically, the only world-economy to have survived for a long time h a s been the modern world-system, and that is because the capitalist system took loot and became consolidated as its defining feature.

Conversely, a capitalist system Cannot exist within any framework except that of a world-economy. We shall see that a capitalist system requires a very special relationship between economic producers and the holders of political power. If the latter are too strong, as in a world-empire, their interests will override those of the economic producers, and the endless accumulation of capital will cease to be a priority. Capitalists need a large market (hence minisystems are too narrolV for them) but they also need a multiplicity of states, so that they can gain the advantages of working with states but also can circumvent states hostile to their interests in favor of states friendly to their interests. Only the existence of a multiplicity of states within the overall division of labor assures this possibility.

A capitalist world-economy is a collection of many institutions, the combination of which accounts for its processes, and all of which are intertwined with each other. The basic institutions are the market, or rather the markets; the firms that compete in the markets; the multiple states, within an interstate system; the households; the classes; and the status-groups (to use Weber’s term, Il’hich some people in recent years have renamed the “identities”) . They are all institutions that have been created within the framework of capitalist world economy. Of course, such institutions have some similantIes to illstltutlOns that eXisted ill prior historical systems o which we have given the same or similar names. But using the same name :0 describe institutions located in different historical systems quite often confuses rather than clarifies analysis. It is better to think of the set of institutions of the modern world-system as contextually specific to it.

Let us start with markets, since these are normally considered the essential feature of a capitalist system. A market is both a concrete local structure in which individuals or firms sell and buy goods, and a virtual institution across space where the same kind of exchange occurs. How large and widespread any virtual market is depends on the realistic alternatives that sellers and buyers have at a given time. In principle, in a capitalist world-economy the virtual market exists in the world- economy as a whole. But as we shall see, there are often interferences with these boundaries, creating narrower and more “protected” markets. There are of course separate virtual markets for all commodities as well as for capital and different kinds of labor. But over time, there can also be said to exist a single virtual world market for all the factors of production combined, despite all the barriers that exist to its free functioning. One can think of this complete virtual market as a magnet for all producers and buyers, whose pull is a constant political factor in the decision-making of everyone-the states, the firms, the households, the classes, and the status-groups (or identities). This complete virtual world market is a reality in that it influences all decision making, but it never functions fully and freely (that is, without interference). The totally free market functions as an ideology, a myth, and a constraining influence, but never as a day-to-day reality.

One of the reasons it is not a day-to-day reality is that a totally free market, were it ever to exist, would make impossible the endless accumulation of capital. This may seem a paradox because it is surely true that capitalism cannot function without markets, and it is also true that capitalists regularly say that they favor free markets. But capitalists in fact need not totally free markets but rather markets that are only partially free. The reason is clear. Suppose there really existed a world market in which all the factors of production were totally free, as our textbooks in economics usually define this-that is, one in which the factors flowed without restriction, in which there were a very large number of buyers and a very large number of sellers, . and in which there was perfect information (meaning that all sellers and all buyers knew the exact state of all costs of production). In such a perfect market, it would always be possible for the buyers to bargain down the sellers to an absolutely minuscule level of profit ( let us think of it as a penny), and this low level of profit would make the capitalist game entirely uninteresting to producers, removing the basic social underpinnings of such a system.

What sellers always prefer is a monopoly, for then they can create a relatively wide margin between the costs of production and the sales price, and thus realize high rates of profit. Of course, perfect monopolies are extremely difficult to create, and rare, but quasi-monopolies are not. What one needs most of all is the support of the machinery of a relatively strong state, one which can enforce a quasi-monopoly. There are many ways of doing this. One of the most fundamental is the system of patents which reserves rights in an “invention” for a specified number of years. This is what basically makes “new” products the most expensive for consumers and the most profitable for their producers. Of course, patents are often violated and in any case they eventually expire, but by and large they protect a quasimonopoly for a time. Even so, production protected by patents usually remains only a quasi-monopoly, since there may be other similar products on the market that are not covered by the patent. This is why the normal situation for so-called leading products (that is, products that are both new and have an important share of the overall world market for commodities) is an oligopoly rather than an absolute monopoly. Oligopolies are however good enough to realize the desired high rate of profits, especially since the various firms often collude to minimize price competition.

Patents are not the only way in which states can create quasi-monopolies. State restrictions on imports and exports (so-called protectionist measures) are another. State subsidies and tax benefits are a third. The ability of strong states to use their muscle to prevent weaker states from creating counterprotectionist measures is still another. The role of the states as large-scale buyers of certain products willing to pay excessive prices is still another.

Finally, regulations which impose a burden on producers may be relatively easy to absorb by large producers but crippling to smaller producers, an asymmetry which results in the elimination of the smaller producers from the market and thus increases the degree of oligopoly. The modalities by which states interfere with the virtual market are so extensive that they constitute a fundamental factor in determining prices and profits. Without such interferences, the capitalist system could not thrive and therefore could not survive.

Nonetheless, there are two inbuilt anti-monopolistic features in a capitalist world-economy. First of all, one producer’s monopolistic advantage is another producer’s loss. The losers will of course struggle politically to remove the advantages of the winners. They can do this by political struggle within the states where the monopolistic producers are located, appealing to doctrines of a free market and offering support to political leaders inclined to end a particular monopolistic advantage. Or they do this by persuading other states to defy the world market monopoly by using their state power to sustain competitive producers. Both methods are used. Therefore, over time, every quasi-monopoly is undone by the entry of further producers into the market.

Quasi-monopolies are thus self-liquidating. But they last long enough (say thirty years) to ensure considerable accumulation of capital by those who control the quasi-monopolies. When a quasi-monopoly does cease to exist, the large accumulators of capital simply move their capital to new leading products or whole new leading industries. The result is a cycle of leading products. Leading products have moderately short lives, but they are constantly succeeded by other leading industries. Thus the game continues. As for the once-leading industries past their prime, they become more and more “competitive,” that is, less and less profitable. We see this pattern in action all the time.

Firms are the main actors in the market. Firms are normally the competitors of other firms operating in the same virtual market. They are also in conflict with those firms from whom they purchase inputs and those firms to which they sell their products. Fierce intercapitalist rivalry is the name of the game. And only the strongest and the most agile survive. One must remember that bankruptcy, or absorption by a more powerful firm, is the daily bread of capitalist enterprises. Not all capitalist entrepreneurs succeed in accumulating capital. Far from it. If they all succeeded, each would be likely to obtain very little capital. So, the repeated “failures” of firms not only weed out the weak competitors but are a condition sine qua non of the endless accumulation of capital. That is what explains the constant process of the concentration of capital.

To be sure, there is a downside to the growth of firms, either horizontally (in the same product), vertically (in the different steps in the chain of production), or what might be thought of as orthogonally (into other products not closely related). Size brings down costs through so-called economies of scale. But size adds costs of administration and coordination, and multiplies the risks of managerial inefficiencies. As a result of this contradiction, there has been a repeated zigzag process of firms getting larger and then getting smaller. But it has not at all been a simple up-and-down cycle.

Rather, worldwide there has been a secular increase in the size of firms, the whole historical process taking the form of a ratchet, two steps up then one step back, continuously. The size of firms also has direct political implications. Large size gives firms more political clout but also makes them more vulnerable to political assault-by their competitors, their employees, and their consumers. But here too the bottom line is an upward ratchet, toward more political influence over time.

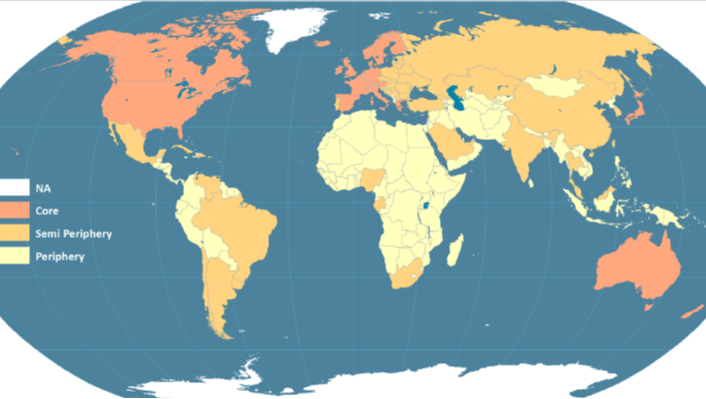

The axial division of labor of a capitalist world-economy divides production into core-like products and peripheral products. Core-periphery is a relational concept. What we mean by core-periphery is the degree of profitability of the production processes. Since profitability is directly related to the degree of monopolization, what we essentially mean by core-like production processes is those that are controlled by quasi-monopolies. Peripheral processes are then those that are truly competitive. When exchange occurs, competitive products are in a weak position and quasi-monopolized products are in a strong position. As a result, there is a constant flow of surplus-value from the producers of peripheral products to the producers of core-like products. This has been called unequal exchange.

To be sure, unequal exchange is not the only way of moving accumulated capital from politically weak regions to politically strong regions. There is also plunder, often used extensively during the early days of incorporating new regions into the world-economy (consider, for example, the conquistadores and gold in the Americas) . But plunder is self-liquidating. It is a case of killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. Still, since the consequences are middle-term and the advantages sho.rt-term, there still exists much plunder in the modern world-system, although we are often “scandalized” when we learn of it. When Enron goes bankrupt, after procedures that have moved enormous sums into the hands of a few managers, that is in fact plunder.

When “privatizations” of erstwhile state property lead to its being garnered by mafia-like businessmen who quickly leave the country with destroyed enterprises in their wake, that is plunder. Self-liquidating, yes, but only after much damage has been done to the world’s productive system, and indeed to the health of the capitalist world-economy.

Since quasi-monopolies depend on the patronage of strong states, they are largely located-juridically, physically, and in terms of ownershipwithin such states. There is therefore a geographical consequence of the core-peripheral relationship. Core-like processes tend to group themselves in a few states and to constitute the bulk of the production activity in such states. Peripheral processes tend to be scattered among a large number of states and to constitute the bulk of the production activity in these states.

Thus, for shorthand purposes we can talk of core states and peripheral states, so long as we remember that we are really talking of a relationship between production processes. Some states have a near even mix of core-like and peripheral products. We may call them semi peripheral states. They have, as we shall see, special political properties. It is however not meaningful to speak of semiperipheral production processes.

Since, as we have seen, quasi-monopolies exhaust themselves, what is a core-like process today will become a peripheral process tomorrow. The economic history of the modern world-system is replete with the shift, or downgrading, of products, first to semiperipheral countries, and then to peripheral ones. If circa 1800 the production of textiles was possibly the preeminent core-like production process, by 2000 it was manifestly one of the least profitable peripheral production processes. In 1800 these textiles were produced primarily in a very few countries (notably England and some other countries of northwestern Europe); in 2000 textiles were produced in virtually every part of the world-system, especially cheap textiles. The process has been repeated with many other products. Think of steel, or automobiles, or even computers. This kind of shift has no effect on the structure of the system itself. In 2000 there were other core-like processes (e.g. aircraft production or genetic engineering) which were concentrated in a few countries.

There have always been new core-like processes to replace those which become more competitive and then move out of the states in which they were originally located. The role of each state is very different vis-a-vis productive processes depending on the mix of core-peripheral processes within it. The strong states, which contain a disproportionate share of core-like processes, tend to emphasize their role of protecting the quasi-monopolies of the core-like processes. The very weak states, which contain a disproportionate share of peripheral production processes, are usually unable to do very much to affect the axial division of labor, and in effect are largely forced to accept the lot that has been given them.

The semiperipheral states which have a relatively even mix of production processes find themselves in the most difficult situation. Under pressure from core states and putting pressure on peripheral states, their major concern is to keep themselves from slipping into the periphery and to do what they can to advance themselves toward the core. Neither is easy, and both require considerable state interference with the world market. These semiperipheral states are the ones that put forward most aggressively and most publicly so-called protectionist policies. They hope thereby to “protect” their production processes from the competition of stronger firms outside, while trying to improve the efficiency of the firms inside so as to compete better in the world market. They are eager recipients of the relocation of erstwhile leading products, which they define these days as achieving “economic development.”

In this effort, their competition comes not from the core states but from other semiperipheral states, equally eager to be the recipients of relocation which cannot go to all the eager aspirants simultaneously and to the same degree. In the beginning of the twenty- first century, some obvious countries to be labeled semiperipheral are South Korea, Brazil, and Indiacountries with strong enterprises that export products (for example steel, automobiles, pharmaceuticals) to peripheral zones, but that also regularly relate to core zones as importers of more “advan ced” products.

The normal evolution of the leading industries-the slow dissolution of the quasi-monopolies-is what accounts fo r the cyclical rhythms of the world-econ omy. A major leading industry will be a major stimulus to the expansion of the world-economy and will result in considerable accumulation of capital. But it also normally leads to more extensive employment in the world-economy, higher wage-levels, and a general sense of relative prosperity. As more and more firms enter the market of the erstwhile quasimonopoly, there will be “overproduction” (that is, too much production for the real effective demand at a given time) and consequently increased price competition (because of the demand squeeze), thus lowering the rates of profit. At some point, a buildup of unsold products results, and consequently a slowdown in fu rther production.

When this happens, we tend to see a reversal of the cyclical curve of the world-economy. We talk of stagnation or recession in the world-economy. Rates of un employment rise worldwide. Producers seek to reduce costs in order to maintain their share of the wo rld market. One of the mechanisms is relocation of the production processes to zones that have historically lower wages, that is, to semiperipheral countries. This shift puts pressure on the wage levels in the processes still remaining in core zones, and wages there tend to become lower as well. Effective demand which was at first lacking because of overproduction now becomes lacking because of a reduction in earnings of the consumers. In such a situation, not all producers necessarily lose out. There is obviously acutely increased competition among the diluted oligopoly that is now engaged in these production processes. They fight each other fu riously, usually with the aid of their state machineries. Some states and some producers succeed in “exporting unemployment” fr om one core state to the others. Systemically, there is contraction, but certain core states and especially certain semiperipheral states may seem to be doing quite well.

The process we have been describing-expansion of the world-economy when there are quasi-monopolistic leading industries and contraction in the world-economy when there is a lowering of the intensity of quasimonopoly- can be drawn as an up-and-down curve of so-called A- (expansion) and B- (stagnati on) phases. A cycle consisting of an A-phase fo llowed 30 Wo rld-Systems Analysis by a B-phase is som etimes referred to as a Kondratieff cycle, after the economist who described this phenomenon with clarity in the beginning of the twentieth century. Kondratieff cycles have up to now been more or less fifty to sixty years in length. Their exact length depends on the political measures taken by the states to ave rt a B-phase, and especially the measures to achieve recuperation fr om a B-phase on the basis of new leading industries that canstimulate a new A-phase.

A Kondratieff cycle, when it ends, never returns the situation to where it was at the beginning of the cycle. That is because what is done in the Bphase in order to get out of it and return to an A-phase changes in some important way the parameters of the world-system. The changes that solve the immediate (or short-run) problem of inadequate expansion of the world-economy (an essential element in maintaining the possibility of the endless accumulation of capital) restore a middle-run equilibrium but begin to create problems fo r the structure in the long run. The result is what we may call a secular trend. A secular trend should be thought of as a curve whose abscissa (or x-axis) records time and whose ordinate (or y-axis) measures a phenomenon by recording the proportion of some group that has a certain characteristic. If over time the percentage is moving upward in an overall linear fa shion, it means by definition (since the ordinate is in percentages) that at some point it cannot continue to do so. We call this reaching the asymptote, or 100 percent point. No characteristic can be ascribed to more than 100 percent of any group. This means that as we solve the middle-run problems by moving up on the curve, we will eventually run into the long-run problem of approaching the asymptote.

Let us suggest one example of how this works in a capitalist world conomy. One of the problems we noted in the Kondratieff cycles is that at a certain point major production processes become less profitable, -a nd these processes begin to relocate in order to reduce costs. Meanwhile, there is increasing unemployment in core zones, and this affects global effective demand. Individual firms reduce their costs, but the collectivity of firms finds it more difficult to find sufficient customers. One way to restore a sufficient level of world effective demand is to increase the pay levels of ordinary workers in core zones, something which has fr equ ently occurred at the latter end of Kondratieff B-periods. This thereby creates the kind of effective demand that is necessary to provide sufficient customers fo r new leading products. But of course higher pay levels may mean lesser profits for the entrepreneurs. At a world level this can be compensated fo r by expanding the pool of wage workers elsewhere in the world, who are willing to work at a lower level of wages. This can be done by drawing new persons into the wage-labor pool, fo r whom the lower wage represents in fact an increase in real income. But of course every time one draws “new” persons into the wage-labor pool, one reduces the number of persons remaining outside the wage-labor pool. There will come a time when the pool is diminished to the point where it no longer exists effectively. We are reaching the asymptote. We shall return to this issue in the last chapter when we discuss the structural crisis of the twenty-first century.

Obviously, a capitalist system requires that there be workers who provide the labor for the productive processes. It is often said that these laborers are proletarians, that is, wage-workers who have no alternative means of support (because they are landless and without monetary or property reserves). This is not quite accurate. For one thing, it is unrealistic to think of workers as isolated individuals. Almost all workers are linked to other persons in household structures that normally group together persons of both sexes and of different age-levels. Many, perhaps most, of these household structures can be called families, but family ties are not necessarily the only mode by which households can be held together. Households often have common residences, but in fact less frequently than one thinks.

A typical household consists of three to ten persons who, over a long period (say thirty years or so) , pool multiple sources of income in order to survive collectively. Households are not usually egalitarian structures internally nor are they unchanging structures (persons are born and die, enter or leave households, and in any case grow older and thus tend to alter their economic role) . What distinguishes a household structure is some form of obligation to provide income for the group and to share in the consumption resulting from this income. Households are quite different from clans or tribes or other quite large and extended entities, which often share obligations of mutual security and identity but do not regularly share income. Or if there exist such large entities which are income-pooling, they are dysfunctional for the capitalist system.

We first must look at what the term ” income” covers. There are in fact generically five kinds of income in the modern world -system. And almost all households seek and obtain all five kinds, although in different proportions (which turns out to be very important) . One obvious form is wage-income, by which is meant payment (usually in money form) by persons outside the household for work of a member of the household that is performed outside the household in some production process. Wage-income may be occasional or regular. It may be payment by time employed or by work accomplished (piecework). Wage-income has the advantage to the employer that it is “flexible” (that is, continued work is a function of the employer’s need), although the trade union, other forms of syndical action by workers, and state legislation have often limited employers’ flexibility in many ways. Still, employers are almost never obligated to provide lifetime support to particular workers. Conversely, this system has the disadvantage to the employer that when more workers are needed, they may not be readily available for employment, especially if the economy is expanding. That is, in a system of wage-labor, the employer is trading not being required to pay workers in periods when they are not needed for the guarantee that the workers are available when they are needed.

A second obvious source of household income is subsistence activity. We usually define this type of work too narrowly, taking it to mean only the efforts of rural persons to grow food and produce necessities for their own consumption without passing through a market. This is indeed a form of subsistence production, and this kind of work has of course been on a sharp decline in the modern world-system, which is why we often say that subsistence production is disappearing. By using such a narrow definition, we are however neglecting the numerous ways in which subsistence activity is actually increasing in the modern world. When someone cooks a meal or washes dishes at home, this is subsistence production. When a homeowner assembles furniture bought from a store, this is subsistence production. And when a professional uses a computer to send an e-mail which, in an earlier day, a (paid) secretary would have typed, he or she is engaged in subsistence production. Subsistence production is a large part of household income today in the most economically wealthy zones of the capitalist world-economy.

A third kind of household income we might generically call petty commodity production. A petty commodity is defined as a product produced within the confines of the household but sold for cash on .a wider market. Obviously, this sort of production continues to be very widespread in the poorer zones of the world-economy but is not totally absent anywhere. In richer zones we often call it free-lancing. This kind of activity involves not only the marketing of produced goods (including of course intellectual goods) but also petty marketing. When a small boy sells on the street cigarettes or matches one by one to consumers who cannot afford to buy them in the normal quantity that is packaged, this boy is engaged in pettycommodity production, the production activity being simply the disassembly of the larger package and its transport to the street market.

A fourth kind of income is what we can generically call rent. Rent can be drawn from some major capital investment (offering urban apartments for rent, or rooms within apartments) or from locational advantage (collecting a toll on a private bridge) or from capital ownership (clipping coupons on bonds, earning interest on a savings account). What makes it rent is that it is ownership and not work of any kind that makes possible the income. Finally, there is a fifth kind of income, which in the modern world we call transfer payments. These may be defined as income that comes to an individual by virtue of a defined obligation of someone else to provide this income. The transfer payments may come fr om persons close to the household, as when gifts or loans are given fr om one generation to the other at the time of birth, marriage, or death. Such transfer payments between households may be made on the basis of reciprocity (which in theory ensures no extra income over a lifetime but tends to smooth out liquidity needs ). Or transfer payments may occur through the efforts of the state (in which case one’s own money may simply be returning at a different moment in time), or through an insurance scheme (in which one may in the end benefit or lose), or through redistribution fr om one economic class to another.

As soon as we think about it, we all are fa miliar with the income-pooling that goes on in households. Picture a middle-class American fa mily, in which the adult male has a job (and perhaps moonlights at a second), the adult fe male is a caterer operating out of her home, the teenage son has a paper route, and the twelve -year-old daughter babysits. Add in perhaps the grandmother who draws a widow’s pension and who also occasionally babysits fo r a small child, and the room above the garage that is rented out. Or picture the working-class Mexican household in which the adult male has migrated to the United States illegally and is sending home money, the adult fe male is cultivating a plot at home, the teenage girl is working as a domestic (paid in money and in kind) in a wealthy Mexican’s home, and the subteen boy is peddling small items in the town market after school (or instead of school). Each of us can elabo rate many more such combinations.

In actual practice, fe w households are without all five kinds of income. But one should notice right away that the persons within the household who tend to provide the income may correlate with sex or age categories. That is to say, many of these tasks are gender- and age-defined. Wa ge-labor was for a long time largely considered the province of males between the ages of fo urteen or eighteen to sixty or sixty-five. Subsistence and petty-commodity production have been fo r the most part defined as the province of adult women and of children and the aged. State transfer income has been largely linked to wage earning, except fo r certain transfers relating to child rearing. Much political activity of the last hundred years has been aimed at overcoming the gender specificity of these definitions.

As we have already noted, the relative importance of the various fo rms of income in particular households has varied widely. Let us distinguish two major varieties: the household where wage-income accounts forr 50 percent or more of the total lifetime income, and the household where it accounts for less. Let us call the fo rmer a “proletarian household” (because it seems to be heavily dependent on wage-income, which is what the term proletarian is su pp osed to invoke ); and let us then call the latter a “semiproletarian household” (because there is doubtless at least some wage-income fo r most members of it). If we do this, we can see that an employer has an advantage in employing those wage-laborers who are in a semiproletarian household.

Whenever wage-labor constitutes a substantial component of household inco m e, there is necessarily a floor fo r how much the wage-earner can be paid. It must be an amount that represents at least a proportionate share of the reproduction costs of the household. This is what we can think of as an absolute minimum wage. If, however, the wage-earner is ensconced in a household that is only semiproletarian, the wage-earner can be paid a wage below the absolute minimum wage, without necessarily endangering the surv ival of the household. The difference can be made up by additional income provided fr om other sources and usually by other members of the household. What we see happening in such cases is that the other producers of income in the household are in effect transferring surplus-value to the employer of the wage-earner over and above whatever surplus-value the wage -earner himself is transferring, by permitting the employer to pay less than the absolute minimum wage.

It fo llows that in a capitalist system employers would in general prefer to employ wage-workers coming fr om semiproletarian households. There are however two pressures working in the other direction. One is the pressure of the wage-workers themselves who seek to be “proletarianized;’ because that in effect means being better paid. And one is the contradictory pressure on the employers themselves. Against their individual need to lower wages, there is their collective longer-term need to have a large enough effective demand in the world-economy to sustain the market for their products. So over time, as a result of these two very different pressures, there is a slow increase in the number of households that are proletarianized. Nonetheless, this description of the long-term trend is contrary to the traditional social science picture that capitalism as a system requires primarily proletarians as workers. If this were so, it would be difficult to explain why, after fo ur to five hundred years, the proportion of proletarian workers is not much higher than it is. Rather than think of proletarianization as a capitalist necessity, it would be more useful to think of it as a locus of struggle, whose outcome has been a slow if steady increase, a secular trend moving toward its asymptote.

There are classes in a capitalist system, since there are clearly persons who are differe ntly located in the economic system with different levels of income who have differing interests. For example, it is obviously in the interest of orkers to seek an increase in their wages, and it is equally obviously in the Intere st of employers to resist these increases, at least in general. But, as we have just seen, wage-workers are ensconced in households. It makes no sense to think of the workers belonging to one class and other members of their household to another. It is obviously households, not individuals, that are located within classes. Individuals who wish to be class-mobile often find that they must withdraw fr om the households in which they are located and locate themselves in other households, in order to achieve such an objective.

This is not easy but it is by no means impossible. Classes however are not the only groups within which households locate themselves. They are also members of status-groups or identities. (If one calls them status-groups, one is emphasizing how they are perceived by others, a sort of objective criterion. If one calls them identities, one is emphasizing how they perceive themselves, a sort of subjective criterion. But . under one name or the other, they are an institutional reality of the modern world- system .) Status-groups or identities are ascribed labels, since we are born into them, or at least we usually think we are born into them. It is on the whole rather difficult to join such groups voluntarily, although not impossible. These status-groups or identities are the numerous “peoples” of which all of us are members-nations, races, ethnic groups, religious communities, but also genders and categories of sexual preferences. Most of these categories are often alleged to be anachronistic leftovers of pre-modern times. This is quite wrong as a premise. Membership in status-groups or identities is very much a part of modernity. Far fr om dying out, they are actually growing in importance as the logic of a capitalist system unfolds further and consumes us more and more intensively. If we argue that households locate themselves in a class, and all their members share this location, is this equally true of status-groups or identities?

There does exist an enormous pressure within households to maintain a common identity, to be part of a single status-group or identity. This pressure is fe lt first of all by persons who are marrying and who are required, or at least pressured, to look within the status-group or identity fo r a partner. But obviously, the constant movement of individuals within the modern world-system plus the normative pressures to ignore status-group or identity membership in fa vor of meritocratic criteria have led to a considerable mixing of original identities within the fr amework of households. Nonetheless, what tends to happen in each household is an evolution toward a single identity, the emergence of new, often barely articulated status-group identities that precisely reify what began as a mixture, and thereby reunify the household in terms of status-group identities. One element in the demand to legitimate gay marriages is this fe lt pressure to reunify the identity of the household.

Why is it so important fo r households to maintain singular class and status-group identities, or at least pretend to maintain them? Such a homogenization of course aids in maintainirig the unity of a household as an in come-pooling unit and in overcoming any centrifugal tendencies that might arise because of internal inequalities in the distribution of consumption and decision making. It would however be a mistake to see this tendency as primarily an internal group defense mechanism. There are important benefits to the overall world-system fr om the homogenizing trends within household structures.

Households serve as the primary socializing agencies of the world -system. They seek to teach us, and particularly the young, knowledge of and respect for the social rules by which we are supposed to abide. They are of course seconded by state agencies such as schools and armies as well as by religious institutions and the media. But none of these come close to the households in actual impact. What however determines how the households will socialize their members? Largely how the secondary institutions fr ame the issues fo r the households, and their ability to do so effectively depends on the relative homogeneity of the households-that is, they have and see themselves as having a defined role in the historical social system. A household that is certain of its status-group identity-its nationality, its race, its religion, its ethnicity, its code of sexuality-knows exactly how to socialize its members. One whose identity is less certain but that tries to create a homogenized, even if novel, identity can do almost as well. A household that would openly avow a permanently split identity would find the socialization function almost impossible to do, and might find it difficult to survive as a group.

Of course, the powers that be in a social system always hope that socialization results in the acceptance of the very real hierarchies that are the product of the system. They also hope that socialization results in the internalization of the myths, the rhetoric, and the theorizing of the system. This does happen in part but never in fu ll. Households also socialize members into rebellion, withdrawal, and deviance. To be sure, up to a point even such antisystemic socialization can be useful to the system by offering an outlet fo r restless spirits, provided that the overall system is in relative equilibrium.

In that case, one can anticipate that the negative socializations may have at most a limited impact on the functioning of the system. But when the historical system comes into structural crisis, suddenly such antisystemic socializations can play a profoundly unsettling role fo r the system.

Thus far, we have merely cited class identification and status-group identification as the two alternative modes of collective expression fo r households. But obviously there are multiple kinds of status-groups, not always totally consonant one with the other. Furthermore, as historical time has moved on, the number of kinds of status-groups has grown, not diminished. In the late twentieth century, people often began to claim identities in terms of sexual preferences which were not a basis for household construction in previous centuries. Since we are all involved in a multiplicity of status groups or identities, the question arises whether there is a priority order of identities. In case of conflicts, which should prevail? Which does prevail?

Can a household be homogeneous in terms of one identity but not in terms of another? The answer obviously is yes, but what are the consequences? We must look at the pressures on households coming from outside. Most of the status-groups have some kind of trans-household institutional expression. And these institutions place direct pressure on the households not merely to conform to their norms and their collective strategies but to give them priority. Of the trans-household institutions, the states are the most successful in influencing the households because they have the most immediate weapons of pressure (the law, substantial benefits to distribute, the capacity to mobilize media) . But wherever the state is less strong, the religious structures, the ethnic organizations, and similar groups may become the strongest voices insisting on the priorities of the households. Even when status-groups or identities describe themselves as antisystemic, they may still be in rivalry with other anti systemic status-groups or identities, demanding priority in allegiance. It is this complicated turmoil of household identities that underlies the roller coaster of political struggle within the modern world-system.

The complex relationships of the world-economy, the firms, the states, the households, and the trans-household institutions that link members of classes and status-groups are beset by two opposite-but symbioticideological themes: universalism on the one hand and racism and sexism on the other.

Universalism is a theme prominently associated with the modern worldsystem. It is in many ways one of its boasts. Universalism means in general the priority to general rules applying equally to all persons, and therefore the rejection of particularistic preferences in most spheres. The only rules that are considered permissible within the framework of universalism are those which can be shown to apply directly to the narrowly defined proper functioning of the world-system.

The expressions of universalism are manifold. If we translate universalism to the level of the firm or the school, it means for example the assigning of persons to positions on the basis of their training and capacities (a practice otherwise known as meritocracy) . If we translate it to the level of the household, it implies among other things that marriage should be contracted for reasons of “love” but not those of wealth or ethnicity or any other general particularism. If we translate it to the level of the state, it means such rules as universal suffrage and equality before the law. We are all familiar with rnantras, since they are repeated with some regularity in public discourse. They are supposed to be the central focus of our socialization. Of course, we know that these mantras are unevenly advocated in various locales of the world-system (and we shall want to discuss why this is so), and we know that they are far from fully observed in practice. But they have become the official gospel of modernity.

Universalism is a positive norm, which means that most people assert their belief in it, and almost everyone claims that it is a virtue. Racism and sexism are just the opposite. They too are norms, but they are negative norms, in that most people deny their belief in them. Almost everyone declares that they are vices, yet nonetheless they are norms. What is more, the degree to which the negative norms of racism and sexism are observed is at least as high as, in fact for the most part much higher than, the virtuous norm of universalism. This may seem to be an anomaly. But it is not.

Let us look at what we mean by racism and sexism. Actually these are terms that came into widespread use only in the second half of the twentieth century. Racism and sexism are instances of a far wider phenomenon that has no convenient name, but that might be thought of as antiuniversalism, or the active institutional discrimination against all the persons in a given status-group or identity. For each kind of identity, there is a social ranking. It can be a crude ranking, with two categories, or elaborate, with a whole ladder. But there is always a group on top in the ranking, and one or several groups at the bottom. These ran kings are both worldwide and more local, and both kinds of ranking have enormous consequences in the lives of people and in the operation of the capitalist worldeconomy.

We are all quite familiar with the worldwide rankings within the modern world-system: men over women, Whites over Blacks (or non-Whites), adults over children (or the aged), educated over less educated, heterosexuals over gays and lesbians, the bourgeois and professionals over workers, urbanites over rural dwellers. Ethnic rankings are more local, but in every country, there is a dominant ethnicity and then the others. Religious rankings vary across the world, but in any particular zone everyone is aware of what they are. Nationalism often takes the form of constructing links between one side of each of the antinomies into fused categories, so that, for example, one might create the norm that adult White heterosexual males of particular ethnicities and religions are the only ones who would be considered “true” nationals.

There are several questions which this description brings to our attention. What is the point of professing universalism and practicing anti-universalism simultaneously? Why should there be so many varieties of anti-universalism? Is this contradictory antinomy a necessary part of the modern world -system?

Universalism and anti- universalism are in fa ct both operative day to day, but they operate in different arenas. Universalism tends to be the operative principle most strongly fo r what we could call the cadres of the worldsystem- neither those who are at the very top in terms of power and wealth, nor those who provide the large majority of the world’s workers and ordinary people in all fields of work and all across the world, but rather an inbetween group of people who have leadership or supervisory roles in various institutions. It is a norm that spells out the optimal recruitment mode for such technical, professional, and scientific personnel. This in-between group may be larger or smaller according to a country’s location in the worldsystem and the local political situation. The stronger the country’s economic position, the larger the group. Whenever universalism loses its hold even among the cadres in particular parts of the world-system, however, observers tend to see dysfunction, and quite immediately there emerge political pressures (both from within the country and from the rest of the world) to restore some degree of universalistic criteria.

There are two quite different reasons fo r this. On the one hand, universalism is believed to ensure relatively competent performance and thus make fo r a more efficient world-economy, which in turn improves the ability to accumulate capital. Hence, normally those who control production processes push fo r such universalistic criteria. Of course, universalistic criteria arouse resentment when they come into operation only after some particularistic criterion has been invoke d. If the civil service is only open to persons of some particular religion or ethnicity, then the choice of persons within this category may be universalistic but the overall choice is not. If universalistic criteria are invoked only at the time of choice while ignoring the particularistic criteria by which individuals have access to the necessary prior training, again there is resentment. When, however, the choice is truly universalistic, resentment may still occur because choice involves exclusion, and we may get “populist” pressure fo r untested and unranked access to position. Under these multiple circumstances, universalistic criteria play a major social-psychological role in legitimating meritocratic allocation. They make those who have attained the status of cadre fe el justified in their advantage and ignore the ways in which the so-called universalistic criteria that permitted their access were not in fa ct fully universal istic, or ignore the claims of all the others to material benefits given primarily to cadres. The norm of universalism is an enormous comfort to those who are benefiting fr om the system. It makes them feel they deserve what they have.

On the other hand, racism, sexism, and other anti-universalistic norms perform equally important tasks in allocating work, power, and privilege 40 Wo rld-Systems Analysis, within the modern world-system. They seem to imply exclusions fr om the s ocial arena. Actually they are really modes of inclusion, but of inclusion at inferior ranks. These norms exist to justify the lower ranking, to enforce the lower ranking, and perversely even to make it somewhat palatable to those who have the lower ranking. Anti- universalistic norms are presented as codifications of natural, eternal verities not subject to social modification.

They are presented not merely as cultural verities but, implicitly or even explicitly, as biologically rooted necessities of the fu nctioning of the human animal. They become norms fo r the state, the workplace, the social arena. But they also become norms into which households are pushed to socialize their members, an effort that has been quite successful on the whole. They justify the polarization of the world -system. Since polarization has been increasing over time, racism, sexism, and other fo rms of anti-universalism have become ever more important, even though the political struggle against such fo rms of anti-universalism has also become more central to the functioning of the world-system.

The bottom line is that the modern world- system has made as a central, basic feature of its structure the simultaneous existence, propagation, and practice of both universalism and anti- universalism. This antinomic duo is as fu ndamental to the system as is the core-peripheral axial division oflabor.

Immannuel Wallerstein, World System Analysis, Duke University Press, 2004, ” The Modern World-System as a Capitalist World- Economy: Production, Surplus-Value, and Polarization”, pp 23-43