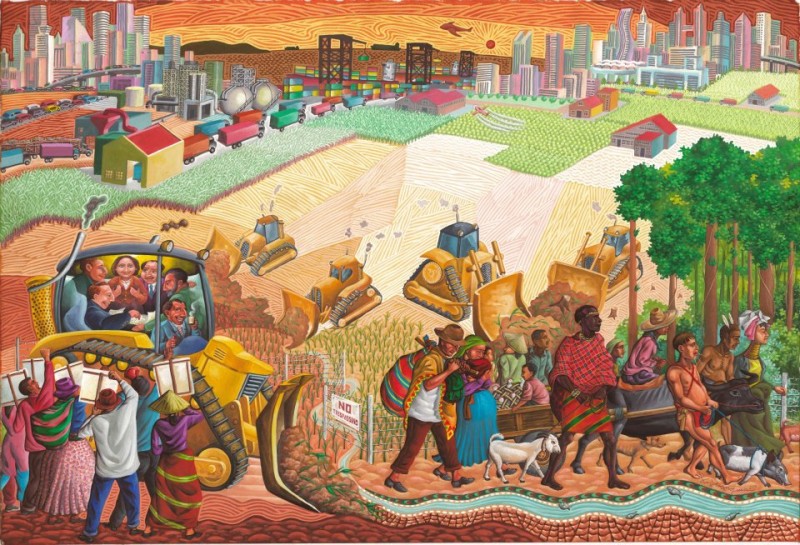

The rise of indigenity politics in 3 Manggaraian Districs (East Nusa Tenggara Province) has a great deal to do with the actual disconnection between development and democracy practices. Development is entirely state’s affairs led by head of districts and local parliaments whose legitimacy and accountability built solely on ballot box. Against this backdrop, indigenity politics emerges particularly as popular responses to the lack of developmental intervention in rural areas of the districts. Popular uprisings in the form of mass protests, boycotts, and ‘illegal’ occupation of mining areas, including series of violent clashes with police have been in the last ten years the ways available for the local people to voicing their demands and discontents. The uprising has twofold message. First, it shows growing popular distrust against the lack of institutional-policy response on the part of the state, and second, simultaneously it projects their attempts at engaging the state as arena of policy making that affects their well-being as rural community. In short, the indigenity politics strongly reflects the sustained effort to render local people visible, recognizable, and capable as citizens of exercising their rights within the existing liberal representation framework.

Indigenity as Arena of Contestation

Indigeneity politics in Manggarai has been marked by the growing involvement of non-state actors at national and local level. Nationwide actors that have played critical role are AMAN (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara), Walhi, and KOMNAS HAM, while local actors include Church based advocacy bureaus and local NGOs operating in three districts. Their active involvement takes place against the background of representative deficit by state actors (local bureaucracy and local parliaments).[1] Various studies have shown how deficit in representation allows greater space for non-state actors to voice popular demand which mainly involve welfare and recognition. In this context, indigenity politics allows non-state actors together with particular rural people to struggle for the realization of their rights as citizen. It is within the current frame of indigeneity politics they start to define their own identity, needs and future projection as they are exposed to market forces and local government complicity.

However, as will be discussed below citizenship articulation through indigenity politics are confronted with problems and challenges. Indigeneity campaign remains entrapped in fixing particular identity of the local people with strong emphasis on being rural, peasantry, and traditional traits. Another weak point of this struggle is its effect on perpetuating the presence of two mutually antagonistic camps between state and non-state actors in addressing rural demands. On the other hand, this study shows indigeneity politics offers fruitful possibility for enhancing democratic articulation by bringing conflicting parties to negotiate their respective agenda and produce common platform in addressing crucial issues in the rural areas. Manggaraian case indicates indigeneity politics should be perceived as a democratic exercise available and in need of upscaling to deepening citizenship and offering new possibilities of governing between local government and citizen.

Anti-Mining Movement and Production of Indigenity Politics

Anti-Mining Movement, as articulator of indigenity politics,has been the leading proponent in representing the rural discontents and demands. It is completely ‘civil society’ movement comprising of local church-based NGOs (JIPC Dioses Ruteng, JIPC SVD, JIPC OFM), nation-wide environmental movement (WALHI), nation-wide Alliance for Indigenous People (AMAN), and also receive growing supports from various academicians, local leaders and educated middle-class in the districts. All these actors advocate rural people affected by the ecological and economic disadvantages of the mining activities. Beside targeting the mining misconducts on the daily basis, the movement calls for the state institutional response and policy-responsibility such as endorsing the heads of the 3 districts to suspend the mining-permits/contracts and also persuade the regents not to issue contracts in years ahead. Although the scope of the issue remains limited to mining, the movement has taken significant role as nodal point of various actors that belong to both development and democracy advocacy. Besides facing dilemma and challenges as will be mentioned in the last part of this session, it provides certain space for popular-rural resistance and ongoing transformation of the power-relation between state, society and market. Political dimension of the movement starts by both assuming rights as given and exercising them to negotiate with state.

Indigenous dimension or becoming indigenous, of the movement evolves as it takes series of collective actions since 2004 onward.[2] Starting with the bloody May event that killed 7 protesters in 2004, discontents and demands of the rural people before the local government and the mining companies began to have been brought within indigenous rights framework following the increasing advocacy taken by AMAN and JIPC. Main reason for the applying the framework is politically strategic to evade the developmental state framework which stresses local government as development actor and rural inhabitants as object of development program intervention.[3] This step benefits the political leverage of the movement as it attracts public attention and endorses local government to take some measure such as suspending mining contracts in West Manggarai and Manggarai Districts, and local governments turn to be more attentive to the movement proposals. Moreover, the crux behind the change in state response lies in the fact that the intelligibility of the movement as advocate of indigenous people directly challenges cultural legitimacy of the local power-holders (regents and local parliaments) whose electoral support and gains largely draw upon their promise as candidates to take care of the well-being of the Roeng (rural-grassroots voters). In effect, being indigenous makes possible the encounter between the state and the movement. Within indigenous rights framework, both parties now seek to take responsibility in fulfilling rural people demands with their respective strengths and limitations. While the notion of indigenous being continuously contested among the parties, one lesson learned is that rural demands begin to gravitate state and public attention, and crystallizes various articulations of poverty reduction and identity recognition campaign.

Under the banner of advocacy for rural-indigenous people,both the movement and local state share slightly different interpretation and actions. The movement puts forward robust agenda for ending all mining in the districts. There are two arguments proposed. First, the mining devastates natural environment upon which rural livelihood has been dependent for generations. Second, the mining erodes cultural world of the indigenous people where land is the center of local cosmology[4]. In short, for the movement, natural exploitation via mining is incompatible with local world view, including Catholic teachings and local demand for economic well-being. On the contrary, the state does not ignore the significance of mining for local development in terms of increasing local revenue and providing jobs for local people. It is also worth noting that mining-contract is legal-binding which gives no space for the government to share the movement robust agenda. On the other hand, welfare rhetoric employed by the state arises from both the limited legal space to maneuver and from the politically antagonistic relation with the movement. It is within this incompatibility of both agendas that representation of indigenous popular demands has for years been facing deadlock and leaving rural-indigenous people entrapped in-between both positions. One of the most apparent risks of the deadlock is the recurrent horizontal conflicts between indigenous communities splitted into state and movement beneficiaries. While becoming more aware of their rights as citizens, current antagonism between both parties makes the movement’s beneficiaries more vulnerable to state’s inaction or discriminate program intervention and prone to getting entrapped in violent conflict escalation.

One of the examples where the notion of indigeneity is articulated and contested between various actors can be found in West Manggarai. In this district, rural people uses indigeneity to defend the notion of place as market force in relation with state actors attempt to transform and develop ‘idle’ areas into a more productive force. At this phase, civil society organizations, both at the local and national, often join, represent, and advocate the local community’s interest through various strategies yet framed by the human rights discourse. One of the most recent examples is the entanglement of power among various actors upon the future development of Pede Beach in West Manggarai. Pede Beach as a potential tourist attraction has attracted some elite, local and national, attention to bring investment. Although at the present such investment has not materialized yet, the rumor has triggered anxiety among local inhabitants, environmental groups, the church, academician and civil society organizations. As a result, various factors have been raised to prevent such business initiative to be implemented further. Environment, place, tradition, culture, economic, and legal are some of the important factors that have been articulated to defend the indigenous rights. Till today, the contestation among various actors continues.

While discussion above illustrates how indigeneity politics enable non-state actors to consolidate when encountering the complicity between the state with market force, in practice indigeneity politics triggers various response from state actors. In other words, there is no single discourse that can be generalized in describing state actors response. Based on the interviews, some bureaucracy express that their support in meeting indigenous rights movement demands is not only due to the consolidation of non-state actors but also because indigeneity politic itself also plays a critical role in shaping the overall landscape of politics in Manggarai.

Local Representatives and Indigenity Politics

Current antagonism between local bureaucracies and anti-mining movement poses one central question regarding to what extend local parliaments has been playing their role as political actors whose representative function is crucial in democratic practice. This study finds out that local representatives are not crucial players in the conflict. There are three features that define their current position. First, the executive power, crystallizing in the overarching authority of Bupati (district regent), downplays the representative role of the local parliament and political parties. Second, current advocacy of indigeneity carried out by church fills representative deficit that should have been performed by the local parliaments. Third, responses from the local parliament, institutional or individual responses, remain fragmented, or less coordinated, and to a certain extent indigenity politics is perceived not as their affairs. These two features characterize their engagement with the indigeneity politics as it will be elaborated below.

Central role of Bupati in conflict over indigeneity claim has sociological, cultural, and political contexts. Being directly elected by the local people allows executive leader to enjoy popular support and symbolic legitimacy in carrying out development programs including winning popular support when in conflict with other parties in matters of public policy. The central sources of local patronage does not rely only on economic and political exchange in terms of jobs, development programs, and loyalty but also bound by local cosmology of leadership. These norms embodied by the sole authority of Bupati as cultural incarnation of leadership. For example, It is against this background, Bupati and local bureaucracy has been able to representing indigeneity in both governmental and cultural framework.

Popular basis of church’s claim of indigeneity politics contributes to the diminishing agency of political parties and local parliaments. Besides seemingly replacing the agency of local parliaments, church advocacy aims to empower its own position and role as dominant institution responding to the ever-growing power of the local bureaucracy. This may partially explain why there has been absence of effort on the part of the church to engage and cooperate with the local parliaments in its struggle for representing indigenous people. This strategy is effective to bring the church back into day to day public affairs or as the sole strategy for its revival. In addition, the ecological reason behind its indigeneity politics allows the church to maintain political disengagement with local parliaments. In short, church indigeneity politics by way of disengaging local parliaments is both inevitable and desirable.

Being institutionally affected and historically entrapped within two conflicting parties in indigenity campaign—the local bureaucracy and the church—local parliaments has been undergoing its own problems and challenges. This study identifies two interconnected problems, relating to first institutional capacity to translate rural people demands into political programs and second the socio-historical articulation which continues to use the logic of individual charismatic figure instead of democratic framework. These two constraints limit the internal cohesion of local parliament agency and its outreach capacity[5]. Active presence of charismatic figures among local parliaments in the discourse of indigenity politics has been the consequence of institutional crisis and gap between local parliament board and political parties.

The extent to which there is a disconnection between local parliament board and political parties affecting its representation deficit in indigenity politics has its sociological roots in electoral process. Indonesian experiment with general election of local parliaments facilitates the inclusion of local-rural actors into political arena in the district cities. Nevertheless, these local-rural representatives often operate individually prior to and post-election therefore left to struggle by its own as political parties agenda often reflects urban bias[6]. This led to a situation where after election, member of parliaments, must negotiate, cope, or utilize the unequal power structure to preserve its own client to secure his or her political career in the future. In other words, each member of parliaments become preoccupied with nurturing and expanding its own clientele network as there are limited alternatives that can provide certainty in a political career. In this political deadlock context, the discourse of indigenity rise to prominence within the political arena.

On another layer, the rural based politicians and parliaments are mostly not member of political parties but whose cultural legitimacy is beneficial for the parties’ constituency and electability. Their rise to power built upon individual achievement and communal proximity[7]. In response to indigenity claim, their engagement is very limited and sporadic as consequence of lack of capacity and understanding of parliamentary agency and lack of responsibility and accountability to rural people which are not part of their electoral constituency. Even worse, those who are representative of the area of indigenity do not always respond to the immediate indigenity claims. Few of them take active part with insufficient support from the institutions and insignificant amount of influence in public debate dominated by local bureaucracy and the church.

Putting aside their ineffective response toward indigeneity claims, members of parliaments reproduce the discourse of indigeneity throughout the electoral process. The emergence of indigeneity as marker of political basis is exploited by rural politician to consolidate internal support in rural areas and to make intelligible the irrelevance of urban-based politicians who desperately seeks to gain votes in the areas mostly using money and aid to customary leaders and church. This indigeneity revival for political purpose turns out to have been one crucial element in the formation of indigeneity discourse in three Manggarai districts since the first general election and direct election of district regent in 2004. As posit by one of the information,

“….you can particularly see in the 2009 local election that the notion of indigeneity was very palpable during election. For example, each village tries to ensure that every village has its representatives because they will represent the clan or family”[8].

Rapid acceptance of indigeneity politics defining anti-mining movement since 2007 is unlikely to happen without years of electoral engagement with indigeneity. What is interesting to note is the fact that while being regularly exploited by the rural politicians, the notion of indigeneity turns out subsequently as a principal articulation available for rural demands.

Constesting Indigenity at Risk

Manggaraian experience with indigenity politics has been a path breaking in the sense that it brings rural people back to both development and democracy discourse. Their demand and identity begin to be visible in the discourse, and the state responsibility and accountability start to be taken as basic parameter of governmental rationality and development programs. It does not stop at bringing back culture into politics as two separate spheres of human activity but most fundamentally, doing politics through cultural articulation that closely engages collective well-being and identity as citizen. With indigenity at hand, politics concerning public matters no longer confined merely into elite affairs but reopening space where practices of exclusion by market penetration and the state’s policy are questioned and debated by both the marginalized and broader segments of citizenship.

Becoming indigenous of the Anti-Mining Movement shows its political nature as it takes places through multilayered processes. At one level, indigeneity enables Anti-Mining movement to make connection between exclusion towards rural people and government’s accountability in carrying out development into a single framework. At another level, indigeneity enhance the anti-mining movement struggle as their movement is broadening up by incorporating the church and national non-governmental organizations. To sustain the notion of indigeneity in articulating Anti-Mining Movement, ecological and customary law reasoning play critical roles in underpinning the spirit of indigenous rights movements.

While Anti-Mining Movement revives the political dimension of indigeneity through advocating rural people demands, the local state, both the executive and legislative also stimulate similar spirit although it undergoes different political paths. For legislative, indigeneity becomes an effective strategy for local parliament members particularly those who originated from rural areas to protect rural interests from urban bias interests. On the other hand, indigeneity strengthen the symbolic legitimacy of Bupati as the political structure is embedded within the local cosmology about leadership. Besides indigenous themselves, church, civil society organization, academician, and politicians have declared their support towards indigenous people’s rights. And while it has brought and to a certain degree revives the political, it has also created an ongoing contestation among various stackholders to claim and define indigeneity.

Manggaraian indigeneity as arena of contestation poses serious question about the future of democratic representation and pro-poor developmental practice. Two possible risks are evident and should be reckoned with democratic framework. First, the continuing contestation over whom or which institution most legitimate for pursuing indigeneity agenda will deepen ideological divide between parties and escalate social tension between their respective proponents, particularly social conflict between acclaimed indigenous communities in rural mining areas. Current lack of hegemonic intervention prolongs has created a certain kind of impasse.

This impasse operates at two levels. First, at the societal level, it fixes social position therefore producing a certain kind of illusion that there is antagonistic relationship inherent between the state and the people. On the longer run, it may strengthen the polarization among various social actors, particularly two leading institutions, the church and the local bureaucracy. On a second layer, it also freezes the local community as indigenous groups therefore limiting their political space and articulation. The possibility to articulate and engage in a broader arena or democratic movement is constrained as this idea is suppressed. With the absence of alternative framework and approach, it is difficult to imagine the transformation into a hegemonic force.

Second risk, consequent to the first, is that in the long-run indigeneity discourse will lose its political radicalness as democratic moment for empowering local representation and building up inter-institution alliance. The erosion is very likely to make it no longer attractive as political signifier for the most affected communities in rural areas. The disenchantment of indigeneity politics stems from two possible directions, first, it is emptied of emancipatory content that has mobilized rural people since the outset of the struggle. Second, it gradually turns to be elite driven discourse upon which two dominant institutions monopolize politics of popular representation to restore their contending legitimacy. This hints at the possible backlash of democratic experiments through indigeneity politics.

Broadening Alliance

These two risks raise more fundamental concern about how best to secure the intricacy, mutually constitutive relation between citizenship and indigenity. Indigenity politics as this study shows has kept alive the dynamics of popular agency through the presence of contending actors. The existing problems and challenges are opportunities to cast new possibilities of rehabilitating the state-church relationship as well as enhancing institutional responsiveness on the part of local parliaments and political parties. To activate popular agency as citizen should move beyond current enclave of resistance into the institutionalization of democratic representation without neglecting the role of non-state actors.

The task ahead is how to broaden alliance between non-state actors and formal institution of representation. This includes bringing together two contrasting discourses, ecology and welfare, into public scrutiny in order to have a common understanding of how best to pursue popular welfare. Welfare arrangement based upon the public deliberation might be very different from what contending parties have proposed through separate practice and mechanism. This study suggests the immediate agenda is to set up new space of encounter between Anti-Mining Movement, Bupati and local bureaucracy, and local parliaments in which joint welfare arrangement and common strategic action are reformulated. With this democratic governance in place all parties including indigenous communities participate with equal standing while acknowledging their respective identities and capacity.

Frans Djalong. Excerpted from Beyond Liberal Politics of Recognition: Bringing Indigenous Rights Movements into DemocraticFramework of Public Policy, Research Report 2015

[1] This information collected from interviews with representatives of the non-state actors mentioned since April to May 2015, in Jakarta and three Manggaraian Districts.

[2] See Beny Denar. Gereja Tolak Tambang. Maumere: Ledalero, 2015; Aleks Jebadu. Tambang: Berkah atau Kutukan. Maumere: Ledalero, 2009; see also, Eman Embu (ed). Gugat! Darah Petani Kopi Manggarai. Maumere: Ledalero, 2004.

[3] Result of FGD with lo15 cal stakeholders in Ruteng, Manggarai District, on 24 May 2015. The stakeholders represented local buraeucray, local representative board, local NGOs, student movements and journalists.

[4] Interview with Marten Jenarut, JIPC-Ruteng Diocese in Ruteng, Manggarai, on 28 May 2015

[5] Interviews with local parliaments, parties’ steering commitees and members of KPUD (Local General Election Commission) in Manggarai and East Manggarai, on 27 May 2015.

[6] Indepth interview with local parliaments from PDI-P in East Manggarai in Borong, on 26 May 2015

[7] Indepth interview with local parliaments from PDI-P, Gerindra and Golkar in West Manggarai, in Ruteng, on 28 May 2015

[8] Interview with local representative from PDI-P in Borong, on 26 May 2015. This views shared by most of the local parliaments and KPUD members interviewed during field research period.