Today, in addressing this session of the United Nations General Assembly, I feel oppressed by a great sense of responsibility. I feel a humility in speaking to this august gathering of wise and experienced statesmen from east and west, from the north and from the south, from old nations and from young nations and from nations newly reawakened from a long sleep. I have prayed to the Almighty that my tongue will find those words which are adequate to express the feelings of my heart, and I have prayed also that these words will bring an echo from the hearts of those who listen.

It is my great pleasure to congratulate the President upon his appointment to his high and constructive office. It is also my great pleasure on behalf of my nation to offer a most heartfelt welcome to the sixteen new Members of the United Nations.

The Holy Book of Islam has a word for us today. The Koran says in my language:

―Hai, sekalian manusia, sesungguhnja Aku telah mendjadikan kamu sekalian dan seorang lelaki dan seorang perempuan, sehingga kamu berbangsa-bangsa dan bersuku-suku, agar kamu sekalian kenal-mengenal satu sama lain. Bahwa sanja jang lebih mulja diantara kamu sekalian ialah, siapa jang lebihtakwa kepadaku.‖

I might translate that as:

―O mankind, I, Allah, made you from a male and a female, and divided you into nations and tribes so that you should come to know one another. In truth, those who are most noble before Allah are ‗those who most are in awe of Allah-and do good works towards Allah.‖ (Surah 49, verse 14.) And the Bible, too, has a word for us: ―Glory to God in the highest: and on earth peace to men of good will.‖ (Luke 2.14.)

I am deeply moved indeed as I survey this Assembly. Here is the proof that generations of struggle have been justified. Here is the proof that sacrifice and suffering have achieved their end. Here is the proof that justice has begun to prevail, and that great evils have already been banished.

Furthermore, as I survey this Assembly, the heart is filled with a great and fierce joy. I see clearly that a new day has dawned, and that the sun of freedom and emancipation, that sun of which we have dreamed so long, is already risen over Africa and Asia.

Now, today I address the leaders of nations and the builders of nations. But, indirectly, I speak also to those you represent, to those who have sent you here, to those who have entrusted their future to your hands. I greatly desire that my words shall strike an echo also in these hearts, in the deep heart of humanity, in that great heart from which has been brought so many shouts of joy, so many cries of sorrow and despair, and so much love and laughter.

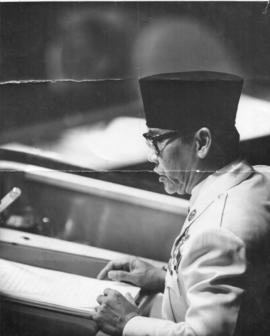

Today, It is President Sukarno who addresses you. But more than that, though, It is a man, Sukarno, an Indonesian, a husband, a father, a member of the human family. I speak to you on behalf of my people, those ninety-two million people of a distant and wide archipelago, those ninety-two million people who have lived a life of struggle and sacrifice, those ninety-two million people who have built a State upon the ruins of an empire.

They, and the people of Asia and Africa, of the American continent and the European continent and the people of the Australian continent, are watching and listening, and hoping.

They see in this Organization of the United Nations a hope for the future and a prospect for the present.

The decision to attend this session of the General Assembly was not an easy one for me to take. My own nation faces many problems, and time to solve those problems is always short.

However, this is perhaps the most important Assembly yet held, and all of us have a responsibility to the rest of the world as well as to our own nations. None of us can escape this responsibility, and surely none wish to. I am very sure that the leaders of the younger and the reborn nations can make a very positive contribution to the solution of the many problems facing this Organization and the world at large. Indeed, I am confident that men may once again say:

The new world is called to redress the balance of the old. It is clear today that all major problems of our world are inter-connected. Colonialism is connected to security; security is connected to the question of peace and disarmament; disarmament is connected to the peaceful progress of the under-developed countries. Yes, all are connected and inter-connected. If we succeed in finally solving one problem, then the way to the solution of all the others will be open. If we succeed in solving, for example, the problem of disarmament, then the necessary funds will be available to assist those nations which so urgently need assistance.

But It is essential that all these problems should solved by the application of agreed principles. Any attempt to solve them by the use of power, or the threat of power, or by the possession of power, will certainly fail, and will in turn produce worse problems. Very briefly, the principle which must be followed is that of equal sovereignty of all nations, which is of course, no more and no less than the application of basic human and national rights. There must be one principle for all nations, and all nations must accept that principle, both for their own protection and for the good of mankind.

If I may say so, we of Indonesia have a very special interest in the United Nations. We have a very special desire to see this Organization flourish and be success. By the actions of this Organization, our own struggle for independence and national life was shortened. I say in full confidence that our struggle would in any case have been successful, but the actions of the United Nations shortened that struggle and saved both us and our opponents many sacrifices and much sorrow and destruction.

Why am I confident that our struggle would have been successful, with or without the activity of the United Nations? I am confident of that for two reasons. First, I know my people: I know their unquenchable thirst for national freedom, and I know their determiation. Secondly, I am confident of that because of the movement of history.

We live, all of us, and everywhere in the world, the time of the building of nations and the breaking of empires. This is the era of emerging nations and the turbulence of nationalism. To close the eyes to this fact is to become blind to history, to ignore destiny and to reject reality.

We live, I say again, in the time of the building of nations. This process is inevitable and certain; sometimes slow-and inevitable, like the movement of molten down the side of an Indonesian volcano; sometimes swift and inevitable, like the bursting of floodwaters from behind an ill-conceived dam. Slow and and evitable, or swift and inevitable, the victory of national struggle is a certainty.

When that march to liberty is complete the whole world over, then our world will be a better place; it will be a cleaner place and a much more healthy place. We must not cease from struggle at this moment, when victory is in sight, but instead we must redouble our efforts. We have a pledge to the future and that must be fulfilled. In this, we do not struggle ourselves alone, but we struggle for all mankind, yes, our struggle is even for those against whom we struggle.

Five years ago, twenty-nine nations of Asia and Africa sent their representatives to the Indonesian city of Bandung. Twenty-nine nations of Asia and Africa. Today, how many free peoples are there? I will count them, but look around this Chamber now. Then tell me whether I am right or not when I way that this is the time of the building of nations, and the time of the emergence of nations. Yesterday, Asia, and that is a process not yet completed. Today, Africa,

and that, too, is a process not yet completed. Furthermore, not all the nations of Asia and Africa are yet represented here. This Organization of nations is weakened in so far as it rejects the representation of any nation, and especially of a nation which is old and wise and powerful.

I speak of China. I speak of what is often called Communist China, which is for us the only real China. This Organization is greatly weakened precisely because it rejects the membership of the biggest nation in the world.

Every year we support the admission of China to the United Nations. We will continue doing that. We do not give our support merely because we have good relations with that country. And certainly we do not do so from any partisan motive. No, our position on this question is guided by political realism. By shortsightedness excluding a vast nation, a nation great and powerful in terms of numbers, culture, the attributes of an ancient civilization, a nation full of strength and economic power, by excluding that nation we make this international Organization much weaker and so much further from our requirements and our ideal.

We are determined to make the United Nations strong and universal and able to fulfill its proper function. that is why we consistently support the representation of China in our number.

Furthermore, disarmament is a pressing need of our world. This most vital of all questions should be discussed and solved within the framework of this Organization. Yet how can there be a realistic agreement on disarmament if China, one of the most powerful nations in the world, is excluded from the deliberations?

Representation of China in the United Nations would involve that nation in constructive world affairs and would thus immensely strengthen this body.

In this year of 1960, the General Assembly again comes together in its annual gathering. But this General Assembly must not be seen merely as another routine meeting, and if It is so regarded, if It is regarded as a routine meeting, then this whole international Organization may well be threatened with dissolution.

Mark my words well, I implore you. Do not treat the problems you will discuss as routine problems. If you do, then this Organization which has afforded us a hope for the future, a prospect of International conciliation, will perhaps be disrupted. It will perhaps disappear slowly beneath the waves Of conflict, as its predecessor did.

If that happens, then humanity as a whole will suffer, and a great dream, a great ideal, will have been shattered. Remember: you do not deal only with words. You do not deal with pawns upon a chessboard. You deal with men, and with the dreams of men, and with the ideals of men, and with the future of all men.

In all seriousness I tell you: we of the newly independent nations intend to fight for the United Nations. We intend to ‗struggle for its success and to make it effective. It can be made effective, and it will be made effective, but only in so far as all its Members recognize the inevitabilities of history. It will be effective only in so far as this body follows the course of history and does not attempt to dam or divert or delay that course.

I have said that this is the time for the building of nations and the breaking of empires. that is most profoundly true. How many nations have achieved their freedom since the Charter of the United Nations was written? How many peoples have thrown off their chains of oppression? How many empires, built upon the oppression of peoples, have crumbled into dust? We, who were voiceless in the past, are voiceless no more. We, who were silent in the misery of imperialism, are silent no more. We, whose struggle for life was cloaked under the mantle of colonialism, are hidden no more.

The world is changed since that historic day in 1945, and It is changed for the better. Out of this era of nation-building has come the -possibility–yes, the necessity-of a world free from fear, free from want, free from national oppressions. Today, this very day, at this General Assembly, we could prepare ourselves for a projection into that future world, the world of which we have thought and dreamed and made visions. We can do that, but only if we do not treat this meeting as routine. We must recognize that the United Nations faces a big accumulation of problems, each of them pressing, each of them a possible threat to peace and peaceful progress.

We are determined that the fate of the world, which is our world, will not be decided above our heads or over our bodies. It will be decided with our participation and co-operation.

Decisions vital to the peace and future of the world can be decided here and now. Here are Heads of State and Heads of Government gathered in one place. There is the framework of our Organization. I very sincerely hope that no questions of rigid protocol, and no narrow feelings of hurt personal or national feelings, will prevent this opportunity from being used fully. A chance

like this does not come often. It should be fully exploited. We have a unique opportunity now for combining private and public diplomacy. Let us grasp that opportunity. It may not come again.

I am very well aware that the presence here of so many Heads of State and Heads of Government meets the hopes of millions of people. They can take vital decisions on establishing a new look for our world, and consequently also a new look for the United Nations.

It is appropriate now to consider the position of the United Nations in relation to this era of nation building and new nationhoods.

I tell you this: for a newly born man or a newly reborn nation, the most precious possession is independence and sovereignty.

Perhaps it may be-I do not know, but perhaps it may be- that this sense of holding the precious jewel of sovereignty and independence is confined to the nations newly awakened.

Perhaps, as generations pass, the sense of pride and achievement grows dim. It may be so, but I do not Think so.

Even today, two hundred years later, is there any American who does not thrill at the words of the Declaration of Independence? Is there any Italian who does not today respond to the call of Mazzini? Is there any citizen of Latin America who does not still hear an echo from the voice of San Martin? Indeed, is there any citizen of the world who does not respond to that call and to those voices? We all thrill, we all respond, because those voices were universal in time and place. They were the voice of suffering humanity; they were the voice of the future, and we hear them still, ringing down the ages.

No, I deeply believe that in sovereignty and national independence There is something which endures something which is as hard and brilliant as a jewel and far more precious. Many nations of this world have long possessed this jewel. They have grown accustomed to owning it, but I am convinced that they still hold it the most dear of their possessions and will die rather than give it up. Is it not so? Would your own nation ever give up its independence? Any nation worthy of the name will die first. Any worthy leader of any nation would die first. How much more precious, then, must It be to us, who once held that jewel of independence and national sovereignty, then felt it snatched from our fingers by well-armed brigands, and have now recovered it for ourselves.

The United Nations is an organization of nation States, each one of which holds that jewel tight and precious. We have all freely banded together as brothers and equals in this Organization – as brothers and as equals, for we all hold equal sovereignty and we all hold that equal sovereignty equally precious.

This is an international body. It is not yet either supranational or supranational. It is an organization of nation States and can function only in so far as It is the will of these nation States that it do so.

Have we unanimously agreed to surrender any part of our sovereignty to this body? No, we have not. We have accepted the Charter, and that Charter is signed by fully sovereign, fully equal, nation States.

It may well be that this body should consider whether its Members should surrender any part of their sovereignty to this international body. But if any such decision is made it must be made freely, unanimously and equally. It must be made by all nations equally-the ancient and the new, the emergent and the old established, the developed and the underdeveloped. This is not something which can be imposed on any nation.

Furthermore, the only possible basis for any body such as this is strict equality. The sovereignty of the newest nation or the smallest nation is just as precious, just as Inviolable as the sovereignty of the largest nation or the oldest nation. And, again, any transgression against the sovereignty of any nation is a potential threat to the sovereignty of all nations.

It is within this world picture that we must regard the world today. Our one world is made up of nation States, each equally sovereign, each resolved to guard that sovereignty and each entitled to guard it. And again I say-I repeat this because It is basic to an understanding of the world today- that we live in an era of nation building. This fact is more important than the existence of nuclear weapons, more explosive than hydrogen bombs and of more potential value to the world than atomic fission.

The balance of the world has changed since that day in June fifteen years ago when the Charter was signed in the United States city of San Francisco, at a moment when humanity was emerging from the horror of war. The fate of humanity can no longer be decided by a few large and powerful nations. We, too,, the younger nations, the burgeoning nations, the smaller nations-we, too, have a word to say, and that word will surely echo down the years.

Yes, we are aware of our responsibility to the future of all nations, and we gladly accept that responsibility. My nation pledges itself to work for a better world, for a world free from strife and tension, for a world in which our children can grow proud and free, for a world in which justice and prosperity reign supreme for all men. Would any nation refuse such a pledge?

Some months ago, just before the leaders of the great Powers met so briefly in Paris, Mr. Khrushchev was our guest in Indonesia. I made it very clear to him that we welcomed the Summit Conference, that we hoped for its success, but that we were skeptical. Those four-great Powers alone cannot decide the questions of war and peace. More precisely, perhaps, they have the power to disrupt the peace, but they have no moral right to attempt, singly or together, to settle the future of the world.

For fifteen years now the West has known peace or at least the absence of war. Of course there have been tensions. Yes, there has been danger. But the fact remains that in the midst of a revolution engulfing three-quarters of- the world the West ha~ been at peace. Both great blocs, in fact, have successfully practiced coexistence for all these years, thus contradicting those who deny the possibility of coexistence. We of Asia have not known peace.

After peace came to Europe we endured atomic bombs. We endured our own national revolution in Indonesia. We endured the torment of VietNam. We suffered the torture of Korea.

We still suffer the agony of Algeria. Is it now to be the turn of our African brothers? Are they to be tortured while our wounds are still unhealed?

And yet the West is still at peace. Do you wonder that we now demand-yes, demandrespite from our torment? Do you wonder that my voice is now raised in protest? We who were once voiceless have demands and requirements; we have the right to be heard. We are not subjects of barter but living and virile nations with a role to play in this world and a contribution to make.

I use strong words, and I use them deliberately, because I am speaking for my nation and because I am speaking before the leaders of nations. Furthermor e, I know that my Asian and African brothers feel equally strongly, although I do not venture to speak on their behalf.

This session of the General Assembly is to be seized of many important matters. No matter, though, can be more important than that of peace. In this respect I am not at this moment speaking of issues arising between the great Powers of the world. Such Issues are of vital concern to us, and I shall return to them later. But look around this world of ours. There are tensions and sources of potential conflict in many places. Look closer at those places and you will discover that, almost without exception, imperialism -and colonialism in one of their many manifestations is at the root of the tension, of the conflict. Imperialism and colonialism and the continued forcible division of nations-I stress those words-is at the root of almost all international and threatening evil in this world of ours. Until those evils of a hated past are ended, there can be no rest or peace in all this world.

Imperialism and the struggle to maintain It-is the greatest evil of our world. Many of you in this hall have never known imperialism. Many of you were born free and will die free. Some of you are born of those nations which have inflicted imperialism on others, but you have never suffered It- yourselves. However, my brothers of Asia and Africa have known the scourges of imperialism. They have suffered it. They know its dangers, its cunning, its tenacity.

We of Indonesia know, too. We are experts on the subject. Out Of that knowledge and out of that experience; I tell you that continued imperialism in any of its forms is a great and continuing danger.

Imperialism is not yet dead. people sometimes say that imperialism and colonialism are dead. No, imperialism is not yet dead. It is dying, yes. The tide of history is washing over its battlements and undermining its foundations. Yes, the victory of independence and nationalism is certain. Still-and mark my, words well-the dying imperialism is dangerous, as dangerous as the wounded tiger in a tropical jungle.

I tell you this-and I am conscious of speaking now for my Asian and African brothers-the struggle for Independence is always justified and always just. •Those who resist that irresistible onward march of national independence and self-determination are blind; those who seek to reverse what is irreversible are dangers to themselves arid to the world.

Until these facts-and they are facts-are recognized, there will be no peace in this world, and no release of tension. I appeal, to you: place the authority and the moral power of this organization of States behind those who struggle for freedom. Do that clearly. Do that decisively. Do that now. Do that, and you will gain the full and wholehearted support of all men of good will. Do that now, and future generations will applaud you. I appeal to you, to all Members of the United Nations: move with the tide of history; do not try to stem that tide.

The United Nations has today the opportunity of building for itself a great reputation and prestige. Those who struggle for freedom will seek support and allies where they can: how much better that they should turn to this body and to our Charter rather than to any group or section of this body.

Remove the causes of war, and we shall be at peace. Remove the causes of tension, and we shall be at rest. Do not delay. Time is short. The danger is great. Humanity the world over cries out for peace and rest, and those things are within our gift. Do not withhold them, lest this body be discredited and deserted. Our task is not to defend this world, but to build the world anew. The future – if There is to be a future- will judge us on the record of our success at this task.

Do not, I beg of you older established nations, underestimate the force of nationalism. If you doubt its force, look around this Chamber and compare it ‗with San Francisco fifteen years ago. Nationalism – victorious, triumphant nationalism – has wrought this change, and it is good.

Today, the world is enriched and ennobled by the wisdom of leaders of sovereign nations newly established. To mention but six examples out of many, There is a Norodom Sihanouk, a Nasser, a Nehru, a Sekou Touré, a Mao Tee Twig in Peiping, and a Nkrumah. Is not the world a better place that they should sit here instead of devoting all their lives and all their strength to the overthrow of the imperialism which bound them? And their nations, too, are free, and my nation is free, and many more nations are free. Is not the world thus a better and a richer place?

Indeed, I do not have to explain to you that we of Asia and Africa are opposed to colonialism and imperialism. More than that, who is there in the world today who will defend those things? They are universally condemned, and rightly so, and the old cynical arguments are no longer heard. Conflict now centres on when colonies are to be free, not on whether they are to be free.

However, I will stress this point: our opposition to colonialism and imperialism comes from both the heart and the head. We oppose it on humanitarian grounds, and we oppose it on the grounds that it presents a great and growing threat to peace.

Our disagreement with the colonial Powers centres on questions of timing and security, for they now pay at least lip service to the ideal of national freedom.

Think deeply, then, about nationalism and independence, about patriotism and about Imperialism. Think deeply, I beg you, lest the tide of history wash over you.

Today, we hear and read much about disarmament. that word refers usually to nuclear and atomic disarmament. Forgive me, please. I am a simple man, and a man of peace. I cannot speak of the details of disarmament. I cannot pass judgment upon rival views concerning inspection, concerning underground testing, and concerning seismographic records.

Upon questions of imperialism and nationalism, I am an expert, after a lifetime of study and struggle, and upon those matters I speak with authority. But upon questions of nuclear warfare, I am just another man, perhaps like the man who lives next door to you, or like your brother or even your father. I share their horror; I share their fear.

I share that horror and that fear because I am part of, this world. I have children, and their future is in danger. I am an Indonesian, and that nation is in danger.

Those who wield those weapons of mass destruction must today face their own conscience, and, finally, perhaps charred to radioactive dust, they must face their Maker. I do not envy them.

Those who are discussing nuclear disarmament must never forget that we, who in this have previously been inarticulate, are watching and are hoping.

We are watching and we are hoping, and yet we are filled with anxiety because, if nuclear warfare devastates our world, we, too, are the sufferers.

No political system, no economic organization, is worth the destruction of the world, including that system or organization itself. If the hydrogen-armed nations alone were involved in this issue, we of Asia and Africa would not care. We would only watch with detachment, filled with wonder that those nations from which we have learned so much, and which we bave admired so much, should today have sunk into such a morass of immorality. We could cry: A curse upon you and we could retire into our own more balanced and peaceful world. But we cannot do that. Already we Asians have suffered atomic bombing. We Asians also are threatened again, and furthermore we feel a moral duty to help in any way we can. We are not the enemies of the East nor of the West. We are part of this world, and we wish to help.

This is a cry from the heart of Asia. Let us help you solve these problems. Perhaps you have looked at them too long, and no longer see them clearly. Let us help you, and in helping you, we will help ourselves, and all the future generations of the world.

It is obvious that the problem of disarmament is not only disagreement on narrow technical grounds. It is a question also of mutual trust. In fact, It is clear that on technical matters and on methods, the two blocks are not very far apart. The problem is rather one of mutual distrust. It is a problem open to solution by methods of discussion and diplomacy. Surely we of Asia and Africa, and the other non-aligned countries, can help in this. We are not short of experience and skill in negotiating. Perhaps our intermediation would be of value. Perhaps we could assist in finding a solution. Perhaps-who knows-we could show you the way to the only real disarmament, which is disarmament in the heart of man, the disarmament of man‘s mistrusts and hatreds.

Nothing could be more urgent than this. And this problem is of such vital importance for the whole of mankind that all of mankind should be involved in. its solution. In fact, I Think we may say now that only pressure and effort from the non-aligned nations will produce the results which the whole world needs. Genuine discussion of disarmament, within this body, and based upon a real desire for success, is essential now. I stress ―within this body‖, for only this Assembly begins to approach a true reflection of the world in which we live.

Think, please, for a moment, of what would be possible if we could evolve a basis for genuine disarmament. Think of the vast funds which would be available for improving the world in which we live. Think of the tremendous impetus which could be given to the development of the underdeveloped, if even only a part of the defence budgets of the great Powers were diverted in that direction. Think of the vast increase in human happiness, human productivity and human welfare, if this were done.

I must add one word on this subject. If There is any greater immorality than the brandishing of hydrogen weapons, then it is the testing of those weapons. I know that There is scientific disagreement about the genetical effect of those tests. that disagreement, however, is in terms of the numbers affected. It is agreed that there are evil genetical effects. have those who authorize the tests ever seen the results of what they do? have they looked at their own children and thought about those results? At the present time, the testing of nuclear weapons is suspended-not, mark you well, forbidden, but only suspended. Let that fact serve as the beginning, then. Let that fact serve as a basis for prohibition of testing, and then for real disarmament.

Before leaving the subject of disarmament, I must make one more comment. To speak of disarmament is good. Seriously to attempt the making of a disarmament agreement would be better. Best of all would be the implementation of an agreement on disarmament. However, let us be realistic. Even the implementation of a disarmament agreement would not guarantee peace to this sore and troubled world. Peace will come only when the causes of tension and conflict are removed.

If there is a cause for conflict, then men will fight with pointed sticks, if they have no other weapon. I know, because my-own nation did that very thing during our struggle for independence. We fought then with knives and pointed sticks. In order to make peace, must remove the causes of tension and of conflict. That is why I spoke deep from my heart about the necessity of co-operation to bring about the final inglorious end of imperialism.

Where there is imperialism, and where there are simultaneously armed forces, then the position is a dangerous one indeed. Again, I speak from experience. What is the situation in West Irian. That is the situation in the one-fifth of our national territory which still labours under imperialism. There in West Irian have imperialism and the armed forces of imperialism.

Bordering that territory, our own troops jtand guard by land and sea. Those two bodies of troops face each other, and I tell you that is an explosive situation. Very recently those young and misguided troops who were in West Irian defending an outmoded conception were reinforced by an aircraft carrier, the Karel Doorman, from their remote homeland. I tell you that then the situation became positively dangerous.

The Commander in Chief of the Indonesian Army sits in my delegation. There he is. His name is General Nasution. He is a professional soldier and an excellent one. Like the soldiers he leads, and like the nation they defend, he is first and foremost a man of peace. More than that, though, he and our-soldiers and my nation are dedicated to the defence of our homeland.

We have tried to solve the problem of West Irian. We have tried seriously and with great patience and great tolerance and great hope. We have tried bilateral negotiations. We tried that seriously, and for years. We tried, and we persevered. We have tried using the machinery of the United Nations, and the strength of world opinion expressed here. We tried, and we persevered with that too. But hope evaporates; patience, tries up; even tolerance reaches an end. They have all run out now, and the Netherlands has left us no alternative but to stiffen our attitude. If they fall correctly to estimate the current of history, we are not to blame. But the result of their failure is that there is a threat to peace, and that involves, once again, the United Nations.

West Irian is a colonial sword poised over Indonesia. It points at our heart, but it also threatens world peace.

Our present determined efforts to reach a solution on our own methods is part of our contribution towards occuring the peace of this world. It is part of our effort to end this world problem of an obsolete evil. It is a determined surgical effort to remove the cancer of imperialism from the area of the world in which we have our life and being.

I tell you in all seriousness, the situation in West Irian is a dangerous situation, an explosive situation; It is a cause of tension and it is a threat to peace. General Nasution is not responsible for that. Our soldiers are not responsible for that. Sukarno is not responsible for that. Indonesia is not responsible for that. No! The threat to peace springs directly from the very existence of colonialism and imperialism.

Remove those checks to freedom and emancipation and the threat to peace disappears. Eradicate imperialism, and the world becomes, -Immediately and automatically, a cleaner place, a better place, a more secure place.

I know that when I say this, the minds of many will turn to the situation in the Congo. You may ask: has not imperialism been ejected from the Congo with the result that there is now strife and bloodshed? It is not so! The deplorable situation in the Congo is caused directly and immediately by imperialism, not by its ending. Imperialism sought to maintain its foothold in the Congo, sought to mutilate and cripple the new State. That is why the Congo is in flames.

Yes, There is agony in the Congo. But that agony is the birth pang of progress, and explosive progress always brings pain. Tearing up the deep roots of vested interests, national and international, always causes pain and dislocation. We know that. We know, too, from our own experience, that development itself creates turbulence. A turbulent nation needs leadership and guidance, and it will eventually produce its own leadership and guidance.

We Indonesians, we speak from bitter experience. The problem of the Congo, which is a problem of colonialism and imperialism, must be solved by application of those principles I have already mentioned. The Congo is a sovereign State. Let that sovereignty be respected.

Remember: the sovereignty of the Congo is no less than the sovereignty of any nation represented in this Assembly, and it must be respected equally.

There must be no interference in the internal affairs of the Congo, and certainly no open or hidden support for disintegration.

Yes, of course, that nation will make mistakes. We all make mistakes, and we all learn from mistakes. Yes, there will be turbulence; but let that go on, too, for it is a sign of rapid growth and development. The extent of that turbulence is a question for the nation itself.

Let us, individually or collectively, assist there if we are requested to do so by the lawful Government of that nation. However, any such assistance must be clearly based upon the unquestioned sovereignty of the Congo.

Finally, have confidence in that nation. They are going through a time of great trial, and are suffering deeply. Eave confidence in them as a newly liberated nation, and they will find their own way to their own solution of their own problems.

I will here utter a very serious warning. Many Members of this body and many servants of this body are perhaps not too well aware of the workings of imperialism and colonialism. They have never experienced it. They have never known its tenacity and its ruthlessness and its many faces and its evil. We of Asia and Africa, we have. I tell you: do not act as the innocent tool of imperialism. If you do, then you will assuredly kill this Organization of the United Nations, and with it you will kill the hope of countless millions and perhaps you will make the future stillborn.

Before leaving these questions, I wish to mention another great issue somewhat similar in nature. I refer to Algeria. Here is a sad picture in which both sides are being bled and ruined for lack of a solution. This is a tragedy! It is quite clear that the people of Algeria want independence. There can be no argument about that. If they had not, then this long and bitter and bloody struggle would have ended years ago. The thirst for independence and the determination to achieve that independence are the central factors in this situation.

What is not yet decided is just how close and harmonious should be the future cooperation with France. Very close and very harmonious co-operation should not be difficult to achieve even at this stage, although perhaps it gets more difficult as the days of struggle pass.

Then let a plebiscite be held under the United Nations in Algeria to determine the wishes of the people on just how close and harmonious those relations should be. The plebiscite should not-again, not-be concerned with the question of independence. That has been settled in blood and tears, and there certainly will be an independent Algeria. A plebiscite such as that I suggest would, if it is held soon, be the best guarantee that independent Algeria and France will have close and good co-operation for their mutual benefit. Again I speak from experience. Indonesia had no intention of disrupting close and harmonious relations with the Netherlands. However, it seems that even today, as generations ago, the Government of that nation insists upon giving too little and asking too much. Only when this became unbearable were those relations liquidated.

Permit me now to turn to the larger issue of war and peace in this world of ours. Very definitely, the new and the reborn nations do not present a threat to world peace. We do not have territorial ambitions; we do not have irreconcilable economic aims. The threat to peace does not come from us, but rather from the older countries, from those long established and stable.

Oh, yes, there is turbulence in our countries. In fact, turbulence almost seems to be a function of the first decade of independence. But is this surprising? Look here, let me take an example from United States history. In one generation we must undergo, as it were, the War of Independence and the War between the States. Furthermore, in that same generation, we must undergo the rise of militant trade–unionism– the period of the International Workers of the World, the Wobblies. We must have our drive to the West. We must have our Industrial Revolution and even, yes, our carpet baggers. We must suffer our Benedict Arnolds. We are, as I have said very often, compressing many revolutions into one revolution and many generations into one generation.

Do you then wonder that there is turbulence amongst us? To us, it is normal, and we have grown accustomed to riding the whirlwind. I understand well that to the man outside often the picture must seem one of chaos and disorder, of coup and counter-coup. Still, this turbulence is our own, and it presents threat to anyone, although often it offers opportunities to interfere in our affairs.

The clashing interests of the big Powers, though are a different matter. There, the issues are obscured by waving hydrogen bombs and by the reiteration of old and worn-out slogans.

We cannot ignore them, for they threaten us. And yet, only too often, they seem unreal. I tell you frankly, and without hesitation, that we put our own future far above the wrangling of Europe.

Yes, we have learned much from Europe and America. We have studied your history and the lives of your great men. We have followed your example we have even tried to surpass you. We speak your languages and we read your books. We have been inspired by Lincoln and by Lenin, by Cromwell, by Garibaldi; and, indeed, we have still much to learn from you in many fields. Today, though, the fields in which we have much to learn from you are those of technique and science, not those of ideas or of action dictated by ideology.

In Asia and Africa today, still living, still thinking, still acting, are those who have led their nations to independence, those who have evolved great liberating economic theories, those who have overthrown tyranny, those who have united their nations, and those who have defeated disruption of their nations.

Thus, and very properly, we of Asia and Africa are turning towards each other for guidance and inspiration, and we are looking inwardly towards the experience and the accumulated wisdom of our own people.

Do you not think that Asia and Africa perhaps -perhaps- have a message and a method for the whole world?

It was the great British philosopher, Bertrand Russell, who once said that mankind is now divided into two groups. One group follows the teachings of Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence. The other group follows the teachings of the Communist Manifesto.

But pardon me, Lord Russell -pardon me- I think you have forgotten something. I think you have forgotten about more than 1,000 million people, the people of Asia and Africa, and possibly also Latin America too, who follow neither the Communist Manifesto nor the Declaration of Independence. Mind you, we admire both, and we have learned much from both, and we have been inspired by both.

Who could fail to be inspired by the words and the spirit of the Declaration of Independence:

―We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.‖

Who, deeply engaged in the struggle for national life and liberty, could fail to be inspired? And again, who amongst us, struggling to establish a just and prosperous society upon the devastation of colonialism, would fail to be inspired by the vision of co-operation and economic emancipation evoked by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels?

Now, there is confrontation between those two outlooks; and this confrontation is dangerous, not only to those who confront each other but also to the rest of the world.

I cannot speak for the rest of Asia and Africa. I am not empowered to do so; and in any case, they are well able to express their own views. However, I am empowered-indeed, instructed-to speak for my own nation of ninety-two million people.

As I say, we have read and studied both of those seminal documents. We have taken much from each and have rejected what is not applicable to us, living in another continent and generations later. We have synthesized what we need from those two documents, and, in the light of experience and in the light of our own knowledge, we have refined and modified that synthesis.

Thus, with apologies to Lord Russell, whom I respect greatly, not all the world is divided into two camps, as he believes.

Although we have extracted from them and although we have sought to synthesize those two great documents, we are not guided only by them. We follow neither the liberal conception nor the communist conception. Why should we? Out of our own experience and out of our own history there has evolved something else, something much more applicable, something much more fitting for us.

The torrent of history shows clearly that all nations need some such conception and ideal. If they do not have it or if it becomes obscured and obsolete, then that nation is in danger.

Our own Indonesian history shows that clearly, and so, Indeed, does the history of the whole world.

We call this ―something‖ PanchaShila. ―Pancha‖ is five; ―shila‖ is principle. Yes, Pancha Shila, or the ―five pillars” T of our State. These five pillars do not spring directly from either the Communist Manifesto or the Declaration of Independence. Indeed, they are ideas and ideals which have, perhaps for centuries, been implicit amongst our people. It is, indeed, not surprising that concepts of great strength and virility should have arisen in our nation during the two thousand years of our civilization and during the centuries of strong nationhood before imperialism engulfed us in a moment of national weakness.

In speaking to you of Pancha Shila, I am expressing the essence of two thousand years of our civilization.

What, then, are those five pillars? They are quite simple: first, belief in God; secondly, nationalism; thirdly, internationalism; fourthly, democracy; and fifthly, social justice. Belief in God; nationalism; Internationalism; democracy; social justice. Very simple. Permit me now to expand a little on those points.

First, belief in God. My nation includes those who follow many different religions: there are Mohammedans, there are Christians, there are Buddhists Indonesia, and there are men of no religion. How ever eighty-five per cent of the ninety-two million people of the Indonesian nation are followers of Islam. Bringing from this fact, and in recognition of the unified diversity of our nation, we place belief in God in the forefront of our philosophy of life. Even those who follow no God recognize, in their innate tolerance, that belief in the Almighty is characteristic of their nation and so accept this first Shila.

Secondly, nationalism. The burning force of nationalism and the desire for independence sustained us and gave us strength during the long colonial night and during the struggle for independence. Today that burning force is still within us and still sustains us. But our nationalism is most certainly not chauvinism. We most certainly do not regard ourselves as superior to other nations. We most certainly do not seek to impose ourselves on other nations. I know well that the word ―nationalism‖ is suspect and even discredited in the West. That is because the West itself has prostituted and distorted nationalism. And yet true nationalism still burns bright in the West. If it had not, then the West would not have challenged with arms the aggressive chauvinism of Hitler.

Does not nationalism-call it, if you will, patriotism-does not that sustain all nations? Who dares deny the nation which bore him? Who dares turn away from the nation which made him?

Nationalism is the great engine which drives and controls all our international activity; It is the great spring of liberty and the majestic inspiration for freedom.

Our nationalism in Asia and Africa is not the same as that of the Western State system.

In the West, nationalism developed as an aggressive force, seeking national economic expansion and advantage. It was the grandparent of imperialism, whose father was capitalism.

In Asia and Africa, and I believe in Latin America also, nationalism is a liberating movement, a movement of protest against imperialism and colonialism, and a response to the oppression of chauvinist nationalism springing from Europe. Asia and African nationalism, and that of Latin America, cannot be considered without reference to its social content.

In Indonesia, we refer to that social content as our drive towards justice and prosperity. Is that not a good aim which all can accept? I do not speak only of ourselves in Indonesia, nor only of my Asian and African and Latin American brothers; I speak of the whole world. A just and prosperous society can, be the aim and the goal of all men.

Mahatma Gandhi once said: ―I am a nationalist, but my nationalism is humanity.‖ We say that too. We are nationalists, we love our nations, and all nations. We are nationalists because we believe that nations are essential to the world in the present day, and we will continue to be so for as far as the eye can see into the future. Because we are nationalists, we support and encourage nationalism wherever we find it.

Our third pillar is internationalism. There is no conflict or contradiction between nationalism and internationalism. Indeed, internationalism cannot grow and flourish except in the rich soil of nationalism. Is not this Organization clear evidence of that? Previously, there, was the League of Nations; now there is the United Nations. The very names proclaim that neither could have existed without the existence of nations and nationalism. And yet the very existence of both shows that the nations desire and need an international body in which each is equal. Internationalism is most certainly not cosmopolitanism, which is a denial of nationalism, which is anti-national and, indeed, anti-reality.

Rather, true internationalism is an expression of true nationalism, in which each nation respects and guards the rights of all nations, big and small, old and new. True internationalism is a sign that the nation has become adult and responsible, forsaking childish ideas of national or racial superiority, forsaking the infantile disorders of chauvinism and cosmopolitanism.

Fourthly, There is democracy. Democracy is not the monopoly or the invention of the Western social orders. Rather, democracy seems to be the natural condition of man, although it is modified to fit particular social conditions.

During the millennia of our Indonesian civilization, we have evolved our own Indonesian democratic forms. It is our belief that these forms have an international relevance and significance. This is a question to which I shall return later.

Finally, the last Shila, the ultimate pillar, is social justice. With this we link social prosperity, for we regard the two as inseparable. Indeed, only a prosperous society can be a just society, although prosperity itself can reside in social injustice.

That, then, is our Pancha Shila: belief in God, nationalism, internationalism, democracy, social justice. Those are the principles which my nation fully accepts and uses as its guide to all political activity, economic activity and social activity.

It is no part of my task today to describe how, in our national life and affairs, we seek to apply and implement Pancha Shila. To do so would be to intrude upon the courtesy of this international body. However, It is my sincere belief that Pancha Shila has much more than a national significance. It has a universal significance and can be applied internationally.

No one will deny the element of truth in the view expressed by Bertrand Russell. Much of the world is so divided between those who accept the ideas and principles of the Declaration of Independence and those who accept the ideas and principles of the Communist Manifesto.

Those who accept one reject the other, and There is conflict on both ideological and practical grounds.

We are all threatened by this conflict, and we are concerned by it. Is there nothing to be done about this threat? Must it continue still for generations, perhaps finally bursting into a flame which will engulf us all? Is there no way out?

There must be a way out. If There is not, then all our deliberations, all our hopes, all our struggles, will be useless. We of Indonesia are not prepared to sit idly back while the world goes to ruin. We are not prepared to have the clear morning of our independence overshadowed by radioactive clouds. No nation of Asia or Africa is prepared to do this. We have a responsibility to the world, and we are ready to accept and fulfill that responsibility. If that means intervening in what have previously been the affairs of great Powers remote from us, thin we are prepared to do that. No nation of Asia or Africa will shirk that task.

Is it not clear that conflict arises chiefly from inequalities? Within the nation, the existence of rich and poor, exploited and exploiters, causes conflict. Remove the exploitation, and the conflict disappears because the cause of conflict has gone. Between the nations, if there are rich and poor, exploiters afl~ exploited, there will also be conflict. Remove that cause of conflict, and the conflict will disappear. that holds good Internationally as well as within the nation The elimination of imperialism and colonialism removes such exploitation of nation by nation.

I believe that there is a way out of this confrontation of ideologies. I believe that the way out lies in the universal application of ―Panca Sila.

Who amongst you rejects Pancha Shila? Do the representatives of the great United States reject it? Do the representatives of the great USSR reject it? Or those of the United Kingdom, or Poland, or France or Czechoslovakia? Or, indeed, any of those who scent to have adopted static positions in this cold war of ideas and practices, who seek to remain rooted deep while the world is in flux?

Look at this delegation who support me and who are sitting here. This is not a delegation of civil servants or professional politicians; this is a delegation representing the Indonesian nation. There are soldiers. They accept Pancha Shila. There is a great scholar of Islam who is a pillar of his faith. He accepts Pancha Shila. There is the leader of the powerful Indonesian Communist Party. He accepts Pancha Shila. There are representatives from the Catholic group and from the Protestant group, from the Nationalist Party and from the organization of workers and peasants. There are women, there are intellectuals and administrators. All of them-yes, all of them-accept Pancha Shila. And they do not accept it merely as an ideological concept, but as a very practical guide to action. Those of my nation who seek to be leaders but reject Pancha Shila are in turn rejected by the nation.

What would be the international application of Panca Sila? How could it work in practice? Let us take the five points one by one.

First, then, belief in God. No person who accepts the Declaration of Independence as a guide to life and action will deny that. And equally certainly, no follower of the Communist Manifesto would, in this international forum today deny the right to believe in the Almighty. For further elucidation about that, I refer to Mr. Aidit, the leader of the Indonesian Communist Party, who is sitting here in my delegation and who accepts whole-heartedly both the Communist Manifesto and the Pancha Shila.

Secondly, nationalism. We are all representatives of nations. How, then, can we reject nationalism? To do so would be to reject our own nations and to reject the sacrifices of generations. But I warn you: if you accept the principle of nationalism, then you must reject imperialism. But to that warning, I will add a reminder: if you reject imperialism, then automatically and immediately you remove from this troubled world a major cause of tension and conflict.

The third point is internationalism. Is it necessary to speak at length about internationalism in this international body? Surely not. If our nations were not internationallyminded, then those nations would not be Members of this Organization. However, true internationalism is not always found here. I regret the necessity of saying that, but it is a fact: true nationalism is not always found here. Only too often the United Nations is used as a forum for narrow national or sectional aims. Only too often the great purposes had high ideals of our Charter-are obscured by the search for national advantage or national prestige. True internationalism must be based upon the fact of national equality. True internationalism must be based upon equality of regard, equality of esteem, the practical application of the truth that all men are brothers. it must, to quote the Preamble of the Charter of the United Nations- that document which is so often forgotten- ‖… reaffirm faith … in the equal rights of nations large and small‖. Finally and once more, internationalism would mean the ending of imperialism and colonialism, and thus it would mean the ending of many dangers and tensions.

Fourth, democracy. For us of Indonesia, democracy contains three essential elements. It contains first the principle of what we call ―mufakat‖, that is unanimity; it contains secondly the prInciple of ―perwakilan‖, that is, representation; finally, it contains for us the principle of ―musjawarah”, and that is deliberation among representatives. Yes, Indonesian democracy contains those three: unanimity, representation, and deliberation among representatives.

These principles of our democratic way of life are deeply enshrined within our people, and have been from time immemorial. They ruled our democratic way of life when wild and savage tribes still roamed over Europe. They guided us when feudalism established itself as a progressive, indeed revolutionary, force over Europe. They gave us strength when feudalism gave birth to capitalism and when capitalism fathered the imperialism which enslaved us. They sustained us during the long eclipse of colonial darkness and during the long slow years when other and different forms of democratic practice were slowly emerging in Europe and America.

Our democracy is old, but it is virile and strong as virile and strong as the Indonesian people from which it sprang.

This organization of United Nations is an organization of States with equal sovereignty, equal independence, and equal pride in that sovereignty and independence. The only way in which it can function satisfactorily is by means of unanimity arising out of deliberation, or, to use the Indonesian terms, by ―mufakat‖ arising from ―musjawarah‖. Deliberations should be held in such a way that there is no contest between opposing points of view, no resolutions and Counter resolutions, no taking of sides, but only a persistent effort to find common ground in solving a problem. From such deliberation there arises a consensus, an unanimity, which is more powerful than a resolution perhaps not accepted, or perhaps resented, by the minority.

Am I talking idealistically? Am I dreaming of an ideal and romantic world? No, I am not.

My feet are firmly planted on the ground. Yes, I look at the skies for inspiration but my head is not in the clouds, tell you that such methods of deliberation work. They work for us; they work in the Indonesian Parliament, They work in the Indonesian National Advisory Council, They work in the Indonesian Cabinet of Ministers. They work because the representatives of our nation desire to make them work. The Communists desire it, the Nationalists desire it, the Moslems desire it, the Christians desire it. The Army desires it, the man in the city and the man in the remote village both desire it; the Intellectual desires it, the man just striving to throw off illiteracy desires it. All desire it, because all desire the clear aim of Pancha Shila, and that clear aim is a just and prosperous society.

Perhaps you may say: ―Yes, we will accept the word of President Sukarno and we will accept the evidence which we see in the composition of his delegation here today, but we are realists in a hard world. The only way to run an international meeting is the way we run the United Nations, with resolutions and amendments and votes of majorities and minorities.‖

Let me tell you something. We know from equally hard, practical, realistic experience that our methods of deliberation work also in international bodies, work also in the international field. They work there equally as well as on the national field.

Look, not so very long ago, as you know, representatives of twenty-nine nations of Asia and Africa met together in Bandung. Those leaders of their nations were no impractical dreamers. Far from it. They were hard, realistic leaders of men and of nations, most of them graduates of the struggle for national freedom, all of them well versed in the realities of political, as well as international, life and leadership.

They were of diverse political outlook, ranging from the extreme left to the extreme right.

Many in the West did not believe that such a conference could produce anything worthwhile. Many even believed that it would break up in confusion and mutual recrimination, torn apart on the rock of political differences.

But the Asian-African Conference succeeded; the Asian-African Conference was conducted by methods of ―musjawarah‖, of deliberation.

There were no majorities, no minorities. There was no voting. There were only deliberations, and only the common desire to reach agreement. Out of that conference came a unanimous communiqué which is one of the most important achievements of this decade, and perhaps one of the most important documents of history.

Can you now still doubt the usefulness and the efficiency of deliberation by such methods?

I am convinced that the wholehearted adoption of such methods of deliberation could ease the work of this international Organization. Yes, perhaps it would make possible the real work of this Organization. It would point the way to solutions of many problems which have accumulated over the years. It would permit the solution of problems which seem to be insoluble.

And remember please that history deals ruthlessly with those who fail. Who today remembers those who toiled in the League of Nations? We remember only those who wrecked that international body. But they wrecked an organization of States from one corner of the world only. We are not prepared to sit back idly and watch this Organization, which is our Organization, wrecked because it is inflexible or because It is slow to respond to changed world conditions.

Is it not worth trying? If you think that it is not, then you must be prepared to justify your decision before the bar of history.

Finally, in the Pancha Shila, there is social justice. To be applied in the International field, this should perhaps be International social justice. Once again, to accept this principle would be to reject colonialism and imperialism.

Furthermore, the acceptance of social justice as an aim by these United Nations would mean the acceptance of certain responsibilities and duties. It would mean a determined, united effort to end many of the social evils which trouble our world. It would mean that aid to the technically under-developed and the less fortunate nations would be removed from the atmosphere of the cold war. It would also mean the practical recognition that all men are brothers and that all men have a responsibility to their brothers.

Is not that a noble aim? Does anyone dare deny the nobility and justice of that aim?

If there is any such, then let him face the reality. Let him face the hungry, let him face the illiterate, let him face the sick, and let him then justify his denial.

Let me now repeat once more those five principles: belief in God, nationalism, internationalism, democracy, social justice.

Let us inquire whether these things do in fact constitute a synthesis which all can accept. Let us ask ourselves whether the acceptance of these principles would provide a solution to the problems faced by this Organization.

Of course, the United Nations consists of more than the Charter of the United Nations.

Nevertheless that historic document remains the guiding star and the inspiration of this Organization.

In many ways, the Charter reflects the political and power constellation of the time of its origin. In many ways that Charter does not reflect the realities of today.

Let us consider then whether the five principles I have enunciated would make our Charter stronger and better.

I believe, yes, I firmly believe that the adoption of those five principles and the writing of them into the Charter would greatly strengthen the United Nations. I believe it would bring the United Nations into line with the recent development of the world. I believe that it would make It possible for the United Nations to face the future refreshed and confident. Finally, I believe that the adoption of Pancha Shila as a foundation of the Charter would make the Charter more whole-heartedly acceptable to all Members, both old and new.

I will make one further point in this direction. It is a great honour to have the seat of the United Nations within one‘s country. We are all grateful indeed to the United States of America that it offered a permanent home to our Organization. However, it might well be questioned whether this is advisable.

With all respect, I submit that it might not be so. The fact that the seat of the United Nations is in the territory of one of the cold-war protagonists has meant that the cold war has worked its way even into the work and the administration and household of our Organization. So much so, indeed, that the very attendance at this session of the leader of a great nation has become a cold war issue, a cold war weapon, and a means of sharpening that dangerous and futile way of life.

Let us inquire whether the seat of our Organization should not be removed from the atmosphere the cold war. Let us inquire whether Asia or Africa or Geneva will offer a permanent home to us, remote from the cold war, uncommitted to either block, and where the representatives can move easily and freely where they will, and in doing so, perhaps gain a understanding of the world and its problems.

I am convinced that an Asian or African country in its faith and belief, would gladly offer hospital to the United Nations, perhaps setting aside a clear area wherein the Organization itself would be sovereign and in which the discussions vital to the vital work could take place in security and brotherhood.

The United Nations is no longer the same body as that which signed the Charter fifteen years ago Nor is this world the same world. Those who labour in wisdom to produce the Charter of this Organization could not have foreseen the shape which it has taken today. Of those wise and far-sighted men, but few realized that the end of imperialism was in sight and that if this Organization was to live it must provide for a great and overbearing and invigorating influx of new and reborn nations.

The purpose of the United Nations should be to solve problems. To use it as a mere debating platform or as a propaganda outlet, or as an extension of domestic politics is to pervert the high ideals which should imbue this body.

Colonial turbulence, the rapid development of the still technically under-developed areas, and the question of disarmament, are still suitable and urgent matters for our consideration and deliberation. However, it has become clear that these vital matters cannot satisfactorily be dealt with by the present Organization of the United Nations. The history of this body demonstrates sadly and clearly the truth of what I say.

It is certainly not surprising that this should be so. The fact is that our Organization reflects the world of 1945, not the world of today. This is so within all its-bodies, except this single august Assembly and in all its agencies.

The organization and membership of the Security Council, that most important body, reflects the economic, military and power map of the world of 1945, when this Organization was born of a vast inspiration and vision. that is also true of most other agencies. They do not reflect the rise of the socialist countries, nor the rocketing of Asian and Africa independence.

In order to modernize and make efficient our Organization, perhaps even the Secretariat, under the leadership of its Secretary-General, may need to be revised. In saying this, I am not, most definitely not, in any way criticizing or denouncing the present Secretary-General who is striving to do a good job under outmoded conditions which must at times seem impossible.

How, then, can they be efficient? How can members of those two groups in the worldgroups which are a reality and must be accepted-how can members of those two groups feel at ease in this Organization, and have the necessary utmost confidence in it?

Since the Second World War, we have witnessed three great permanent phenomena.

First is the rise of the socialist countries. That was not foreseen in 1945. Second is the great wave of national liberation and economic emancipation which has swept over Asia and Africa and over our brothers in Latin America. I think that only we who were directly involved anticipated that. Third is the great scientific advance, which at first dealt in weapons and war, but which is turning now to the barriers and frontiers of space. Who could have prophesied this?

It is true that our Charter can be revised. I am aware that there exists a procedure for doing so, and a time when it can be done. But this question is urgent. It may be a matter of life and death for the United Nations. No narrow legalistic thinking should prevent this being done at once.

Equally it is essential that the distribution of seats in the Security Council and the other bodies and agencies should be revised. I am not thinking in this matter in terms of block votes, but I am thinking of the urgency that the Charter of the United Nations, of the United Nations bodies, and its Secretariat should all reflect the true position of our present world.

We of Indonesia regard this body with great hope and yet with great fear. We regard it with great hope because it was useful to us in our struggle for national life. We regard it with great hope because we believe that only some such organization as this can provide the framework for the sane and secure world we crave. We regard it with great fear, because we have presented one great national issue, the issue of West Irian, before this Assembly, and no solution has been found. We regard it with fear because great Powers of the world have introduced their dangerous cold war game into its halls. We regard it with fear lest it should fail, and go the way of its predecessor, and thus remove from the eyes of man a vision of a secure and united future.

Let us face the fact that this Organization, in its present methods and by its present form, is a product of the Western State system. Pardon me, but I cannot regard that system with reverence. I cannot even regard it with very much affection, although I do respect it greatly.

Imperialism and colonialism were offspring of that Western State system, and in common with the vast majority of this Organization, I hate imperialism, I detest colonialism, and I fear the consequences of their last bitter struggle for life. Twice within my own lifetime the Western State system has torn itself to shreds, and once almost destroyed the world, in bitter conflict.

Can you wonder that so many of us look at this Organization, which is also a product of the Western State system, with a question in our eyes? Please, do not misunderstand me. We respect and admire that system. We have been inspiredby the words of Lincoln and of Lenin, by the deeds of Washington and by the deeds of Garibaldi. Even, perhaps, we look with envy upon some of the physical achievements of the West. But we are determined that our nations, and the world as a whole, shall not be the play thing of one small corner of the world.

We do not seek to defend the world we know: we seek to build a new, a better world! We seek to build a world sane and secure. We seek to build a world in which all may live in peace. We seek to build a world of justice and prosperity for all men. We seek to build a world in which humanity can achieve its full stature.

It has been said that we live in the midst of a revolution of rising expectations. It is not so. We live in the midst of a revolution of rising demands. Those who were previously without freedom now demand freedom. Those who were previously without a voice now demand that their voices be heard. Those who were previously hungry now demand rice, plentifully and every day. Those who were previously unlettered now demand education.

This whole world is a vast power house of revolution, a vast revolutionary ammunition dump. No less than three-quarters of humanity is involved in this revolution of rising demands, and this is the greatest revolution since man first walked erect in a virgin and pleasant world.

The success or failure of this Organization will be judged by its relationship to that revolution of rising demands. Future generations will praise us or condemn us in the light of our response to this challenge.

We dare not fail. We dare not turn our backs on history. If we do, then we are lost indeed. My nation is determined that we shall not fall. I do not speak to you from weakness; I speak to you from strength. I bring to you the greetings of ninety-two million people, and I bring to you the demand of that nation. We have now the opportunity of building together a better world, a more secure world. That opportunity may not come again. Grasp it, then, hold it tight, use it.

No man of good will and integrity will disagree with the hopes and beliefs I have expressed, on behalf of my nation, and indeed on behalf of all men. Let us then seek, immediately and with no further delay, the means of translating those hopes into realities.

As a practical step in this direction, it is my honour and my duty to submit a draft resolution to this General Assembly. On behalf of the delegations of Ghana, India, the United Arab Republic, Yugoslavia and Indonesia, I hereby submit the following draft resolution:

―The General Assembly,

“Deeply concerned with the recent deterioration in international relations which threatens the world with grave consequences,

“Aware of the great expectancy of the world that this Assembly will assist in helping to prepare the way for the easing of world tension,

“Conscious of the grave and urgent responsibility that rests on the United Nations to initiate helpful efforts,

“Requests, as a first urgent step, the President of the United States of America and the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to renew their contacts interrupted recently, so that their declared willingness to find solutions of the outstanding problems by negotiation may be progressively implemented.‖

May I request, on behalf of the delegations of the aforementioned five nations that this draft resolution receive your urgent consideration. A letter to this effect, signed by the heads of the delegations of Ghana, India, the United Arab Republic, Yugoslavia and Indonesia, has already been sent to the Secretariat.

I submit that draft resolution on behalf of those five delegations and on behalf of the millions of people in those nations.

To accept this resolution is a possible and immediate step. Let this General Assembly accept this resolution as soon as possible. Let us take this practical step towards an easing of the dangerous tension in our world. Let us carry this resolution unanimously, so that the full force of the world‘s concern may be felt. Let us take this first step, and let us determine to continue our activity and pressure until our world becomes the better and more secure world we envisage.

Remember what has gone before. Remember the struggle and the sacrifice we newer Members of this Organization have undergone. Remember that our travail was caused and prolonged by rejection of the principles of the United Nations. We are determined that it shall not happen again.

Build the world a new. Build it solid and strong and sane. Build that world in which all nations exist in peace and brotherhood. Build the world fit for the dreams and the ideals of humanity. Break now with the past, for the day is at its dawning. Break now with the past, so that we can justify ourselves with the future.

I pray that God Almighty will bless and guide the deliberations of this Assembly.